Police and outreach workers in Cincinnati work together in overdose trouble spots in a program designed as a model for other communities.

Tall grass, dirty clothes and weeds poke from muddy ground where at one time there was a lawn in East Price Hill. Uncapped syringes do, too.

They are stuck among strewn shards of glass and empty, crushed energy drink bottles. There’s a red wig, some broken seating. And an opened box labeled Narcan, perched on the brick porch railing at 1120 Carson Ave.

Cincinnati firefighters were here on Aug. 5 to revive someone who’d overdosed, likely on fentanyl. The vacant house, next to a scrubbed-clean, navy-blue painted brick home accented with an American flag, is on the radar of neighborhood police officers, firefighters, outreach workers and others.

The faces of a crisis:Lives lost to overdose as opioid epidemic surges through Ohio, fueled by fentanyl

They are working to break overdose cycles, to save lives and change the environment so those who get well can flourish in the neighborhood they call home.

Sgt. Jacob Hicks of the Cincinnati Police District 3 Neighborhood Liaison Unit yells through a broken window: “Cincinnati police. Call out if you’re there.” He has no intention to make arrests. Next to him, Tony Wilson, a Crossroads Center outreach worker in recovery from alcohol use disorder, stands by ready to politely talk to anyone who emerges.

No one comes out. The pair leaves the disheveled site. It won’t look like this for long. Police will get in touch with the landlord. Openings will be boarded up or fixed, trash removed. Grass cut. City services and the Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority will take over if that’s necessary, Hicks says, and the house could be fixed up and re-sold.

'The ease of access is terrifying':Fake prescription pills kill kids, inexperienced users in latest version of epidemic

But if anyone returns to sleep here or use drugs before then, they will see a pamphlet that Wilson left in the broken window frame, or they might find a card he tucked into an entryway. A way to say, hey, need anything? Call me.

The visit to Carson Avenue is one of endless, tightly focused efforts to prevent overdoses, provide continuing care and services to individuals with addiction and fix festering problems that could reignite addiction illness in Cincinnati Police District 3.

Healing Cincinnati neighborhoods from overdose

It is a plan loosely identified as the District 3 neighborhoods' hotspots program, a project that started in East Price Hill on Oct. 1, 2021, with a National Institutes of Health Healing Communities Study grant of $188,360, and gradually was expanded through the district.

The Healing Communities Study is an effort to integrate evidence-based prevention, treatment and recovery interventions to reduce opioid overdose deaths by 40% over three years in communities in states including Ohio and Kentucky.

Fentanyl on the rise in Ohio: Flood of fentanyl hits Cincinnati region with fake prescription pills

The idea, said Newtown Police Chief Tom Synan, who spearheaded the local project, is to meet people with addiction where they are – “but not to then leave them there.”

The goal is to continue the program here and make it a model for other communities, he said.

Even after the grant for the hotspots project ended on June 30, the work continues. And it has expanded.

“It can’t end,” said Synan, a local, national and international voice for evidence-based treatment in lieu of jail for people with addiction disorder, and a coordinator with the Hamilton County Addiction Response Coalition.

The hotspots program is a way to take police and fire data, formulated from their calls for service, and figure out ways to pinpoint the most troubled spots in a neighborhood – locations where people overdose the most, homeless camps, petty crime sites, vacant homes – and bring relief.

It started after Synan spoke with Wilson, a Delhi father of four who, before his recovery once lived and hung out in the Price Hill neighborhoods.

'Doctors cannot be part of the problem':More doctors charged with illegally prescribing pain pills in multistate effort by feds

Wilson told Synan that one of the major problems with efforts to fix addiction is that those with a drug use disorder often return to an environment that hasn’t changed. Help is nowhere to be found. And they relapse.

“That’s what I did,” Wilson said. “And it got bad real quick.”

“We were working part time on a full-time problem,” Synan said. Providing harm reduction or offering treatment, but not really pulling people through to a sustained recovery.

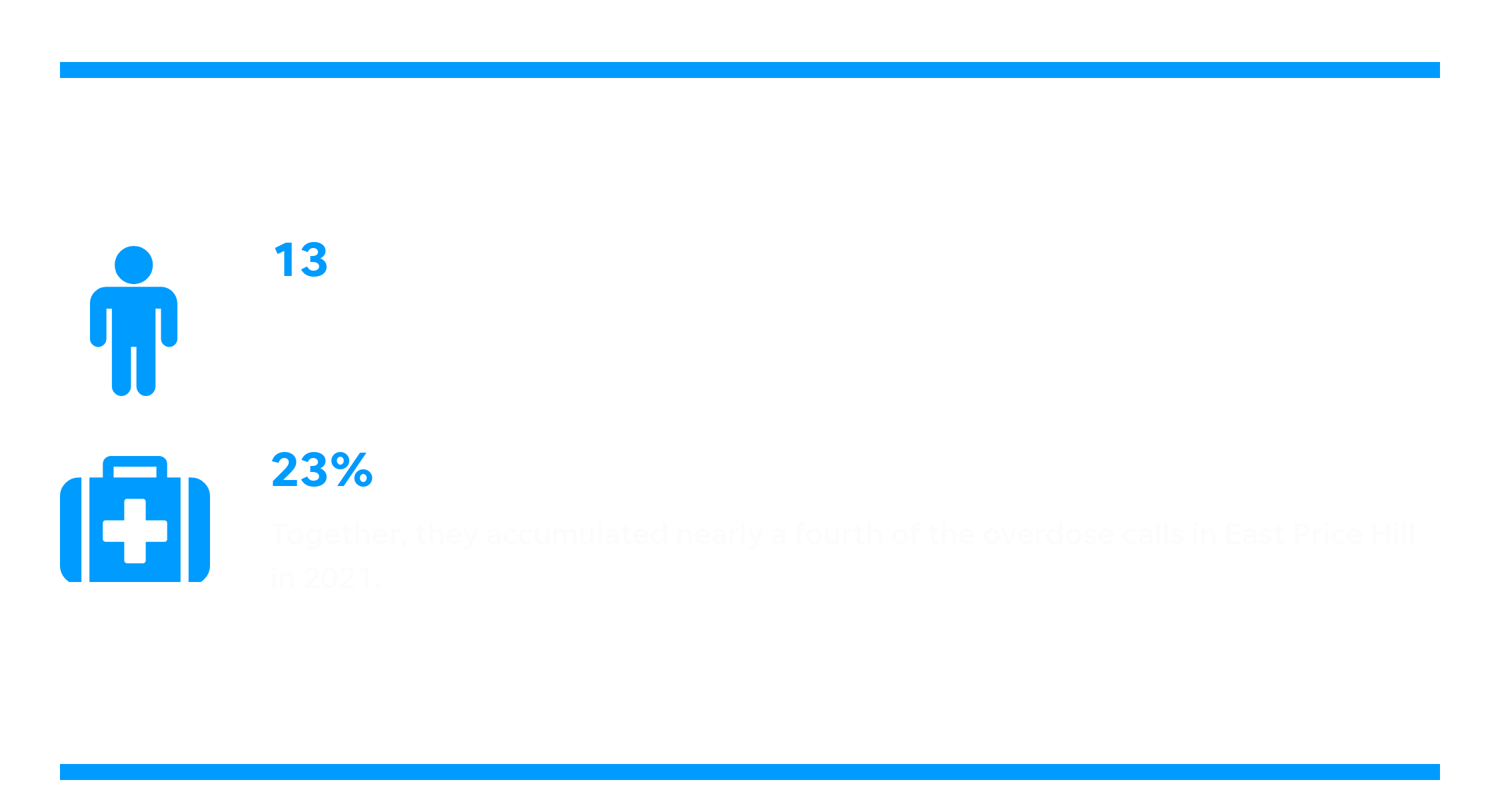

Identifying 13 people who suffered 23% of known East Price Hill overdoses

Among the first efforts the hotspots team took on was identifying the people most likely to overdose in East Price Hill.

Through analysis of overdose calls in the neighborhood, 13 individuals were identified and selected for wrap-around services. Together, they had accumulated nearly a fourth (23%) of the overdose calls in East Price Hill in 2021, said Meagan Gosney, Hamilton County Addiction Response Coalition program coordinator.

'A really scary moment': Young people's overdose deaths jumped in 2020, so, what now?

The work is methodical. It is not easy, but the outreach workers do not give up.

The middle-aged man was living in a high-density crime zone with two roommates who also used drugs. Their apartment itself was the zone: a trouble spot for drug-related calls.

Sara Coyne, among the Hamilton County’s Quick Response Team members, reached out to the man, and heard nothing.

Again and again, Coyne tried to make him see her, calling him, trying to engage him on social media, visiting the apartment on Werk Road to connect with him.

Neighborhood report: East Price Hill

Did he need anything? Any kind of help? I’m Sara. I can help.

Finally he responded. “You’re a persistent bitch, aren’t you?” he said. But the encounter proved to be a successful start to a mutually respectful relationship, team members say.

Coyne offered him lifesaving Narcan, and he was grateful for it.

Gradually, the man came to trust her. And it wasn’t long before he decided he wanted to get well.

Success is just taking that step toward a new life. Getting Narcan. Taking a fentanyl test strip (kit).

With Coyne’s help, he gets medication for opioid use disorder now. He has a job. He remains connected with Sara, and to any services he may need.

He is healthy.

Not all the initial 13 people have taken the help.

But the hotspots team has seen their work pay off.

Three people are getting medication for opioid use disorder. Among them is a 32-year-old woman. A 44-year-old man is now employed, and he’s continued getting harm reduction help. Three were jailed, and their workers will be there for them upon their release.

Fentanyl in Hamilton County: Lab confirms powder form of colorful rainbow fentanyl now in southwest Ohio

Documented overdoses among these initial 13 people have dropped 72.4% this year, Gosney said. The decrease in overdose runs has saved the city $36,750, she said.

And the hotspots team has expanded the number of people it’s identified for help to 19, ranging from a 19-year-old Black man to a 73-year-old white woman.

Collecting data, zeroing in on Cincinnati overdose hotspots

Rachel Kleindorfer, a Cincinnati Police data analyst, repeatedly combs the police and fire calls and area complaints. What parts of District 3 have the greatest need for help? Where are calls coming from? She adjusts or expands areas to be targeted for response as the calls for service change over time. Kleindorfer comes up with one fat packet after another of papers loaded with graphs and street maps and data that the team can use to find isolated problem areas.

Among the calls she follows are those about disorder, assaults, criminal damaging, prostitution and, of course, overdose. Everyone on the team is given the packet. Monthly, members of the District 3 response team discuss how to approach the situations at hand. And they respond.

Dan Gerard, formerly a District 3 police captain who’s volunteered to help strategize for the program, said the work is fundamentally different from traditional police response.

“Historically, we would deal with the immediate issue at hand ∸ opioid use disorder, prostitution, other quality-of-life issues ∸ and quickly move onto the next. We’d merely disrupt the activity for a time, and it came back later, either at the same location or in the immediate vicinity, causing us to do it all over again,” Gerard said. “This new model is based on dismantling the opportunity structure so that the activity doesn’t occur again.”

Tips for parents: How to keep your kids safe from counterfeit prescription pills

Instead of arresting people for having syringes or a small amount of drugs, or shooing people to another part of the neighborhood, police partner with outreach workers to help those in need.

It’s a shift in police philosophy, Gerard said, “and a fundamental recognition they cannot arrest their way out of the problem of opioid use disorder.”

One area dense with persistent crime is Warsaw Avenue in East Price Hill.

Reaching out to support those struggling with addiction

Sgt. Hicks’ Neighborhood Liaison Unit and Wilson make their presence known here.

On a muggy August afternoon, Wilson approaches a woman with multicolored dyed hair who’s lingering on the street. The shorts she wears reveal dark, circular bruises on her legs.

She’s willing to chat, says her name is Taylor.

Wilson talks with the woman for a while. She acknowledges she uses “heroin,” and stays to hear how he can help. He mentions Crossroads Center. “They have got inpatient treatment, outpatient treatment and sober living,” he tells her.

I helped get a young man who overdosed four times last year into treatment.

Taylor nods, takes Tony’s card and points out a man across the street, saying he’s “a big heroin addict.” Tony takes the signal. He might never see her again.

But you never know, he says.

Fentanyl on the rise in Ohio: Traffickers using 'rainbow fentanyl' which looks like candy to target youth, DEA warns

“I helped get a young man who overdosed four times last year into treatment,” he says.

He’d met the man in the same area while out with Hicks, and made a connection. Afterward, Wilson talked to the man on the phone a few times. And in April, the man entered a methadone program.

Defining success for Hamilton County Addiction Response Coalition

Scott Robinson, 52, is an Ohio Highway Patrol trooper from the Hamilton post. He’s worked as a trooper for 29 years. His role now is engaging with people who use drugs through the Hamilton County Quick Response Team.

Robinson sits with another team member, Sheryl Miles, 30, a peer navigator, at a table they’ve set up at Revive City Church on McPherson Avenue one day in July. It’s loaded with Narcan, fentanyl test strips, hygiene kits and other items that people who use drugs might want to use to stay safe. Robinson and Miles are there to greet people, to offer them help, and try to lead them to treatment and other services.

“Just them having a conversation with you is a success,” Miles says. “Success is just taking that step toward a new life. Getting Narcan. Taking a fentanyl test strip (kit).”

You have to be patient, Robinson said.

What's being done? Black opioid overdose deaths soar in Ohio, Kentucky, study shows

“When they’re not ready for treatment, we try to see, will they connect on Facebook? By phone? We call and check on them,” Robinson said. “You build a rapport with them.”

Synan said initially successes are small, but the goal is always to provide care, fill gaps in services, help people not just into recovery but into sustained recovery. “I understand meeting people where they are, but we can’t just leave them there. Especially in environments that take advantage of them and help to continue the cycle of addiction. We should set long-term goals, not just to revive people, or to hand them off, or to get them to treatment,” Synan said.

We need to fill the gaps, so that when people fall, we catch them.

The work suits Robinson. He grew up in Hamilton, in Butler County, raised by his grandmother, and has seen addiction up close. He’s been a full-time Quick Response Team member for a year now. “I didn’t like going out and arresting people.”

Synan said Cincinnati Police District 3 is just the first iteration of the hotspots project. This is a program he says will be modeled by other communities.

A model program?

“We will tailor it to each hotspot community’s unique needs,” Synan said.

“This project taught us that we cannot ‘blanket’ our response,” he said. “Instead, we need to take in all the community factors that keep someone in the addiction cycle within a specific location, wrap needed resources and services right down to the neighborhood, individual street or person.

Addiction response:Hamilton County overdose-prevention efforts expand work, face-to-face strategies in 2021

“We need to fill the gaps,” Synan said, “so that when people fall, we catch them.”