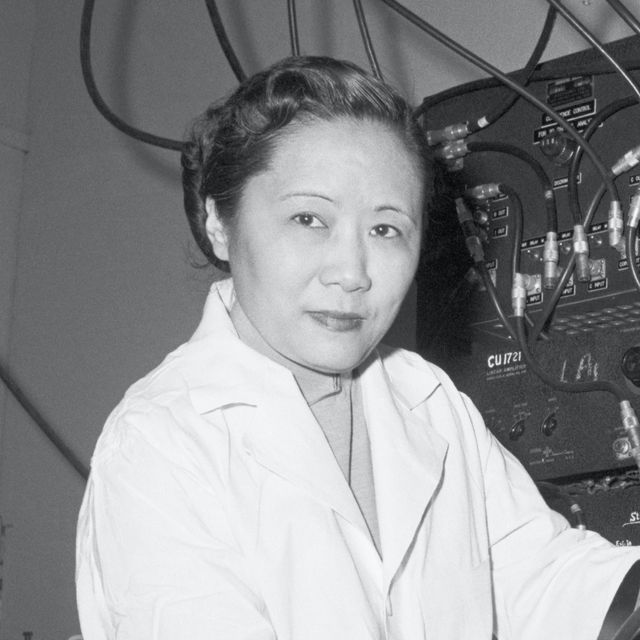

(1912-1997)

Who Was Chien-Shiung Wu?

Chien-Shiung Wu was a Chinese-American nuclear physicist who has been dubbed "the First Lady of Physics," "Queen of Nuclear Research" and "the Chinese Madame Curie." Her research contributions include work on the Manhattan Project and the Wu experiment, "which contradicted the hypothetical law of conservation of parity." During her career, she earned many accolades including the Comstock Prize in Physics (1964), the Bonner Prize (1975), the National Medal of Science (1975), and the Wolf Prize in Physics (inaugural award, 1978). Her book Beta Decay (1965) is still a standard reference for nuclear physicists. Wu died in 1997 at the age of 84.

Early Life and Education

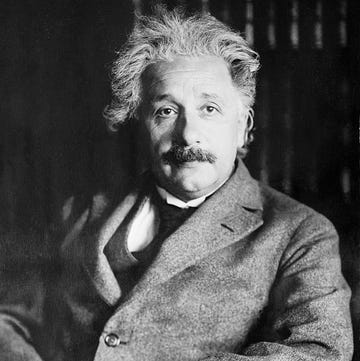

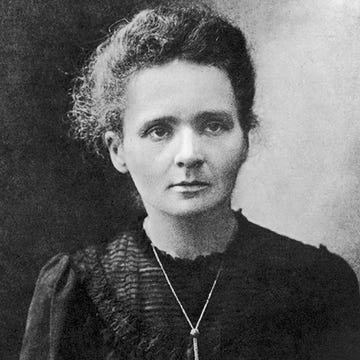

Born in the small town of Liu He (Ho) located near Shanghai, China, on May 31, 1912 to Zhong-Yi and Fanhua Fan, Chien-Shiung Wu was the only daughter and middle child of three children. Education was important to the Wu family. Her mother, a teacher, and her father, an engineer, encouraged her to pursue science and mathematics from an early age. She attended one of the first elementary schools that admitted girls, Mingde Women's Vocational Continuing School, which was founded by her father, and after that, she left to attend the boarding school, the Soochow (Suzhou) School for Girls and enrolled in the Normal School teaching program. Later she attended Shanghai Gong Xue public school for one year. In 1930, Wu enrolled in one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions of higher learning in China, Nanjing (or Nanking) University, also known as National Central University, where she first pursued mathematics but quickly switched her major to physics, inspired by Marie Curie. She graduated with top honors at the head of her class with a B.S. degree in 1934.

After graduation, she taught for a year at the National Chekiang (Zhejiang) University in Hangzhou and worked in a physics laboratory at the Academia Sinica where she conducted her first experimental research in X-ray crystallography (1935-1936) under the mentorship of Jing-Wei Gu, a female professor. Dr. Gu encouraged her to pursue graduate studies in the United States and in 1936, she visited the University of California at Berkeley. It was there she met Professor Ernest Lawrence, who was responsible for the first cyclotron and who later won a Nobel Prize, and another Chinese physics student, Luke Chia Yuan, who influenced her both to remain at Berkeley and obtain her Ph.D. Wu's graduate work focused on a highly desirable topic of that era: uranium fission products.

Academic Career

After completing her Ph.D. in 1940, Wu married fellow former graduate student, Luke Chia-Liu Yuan on May 30, 1942, and the two moved to the East coast where Yuan worked at Princeton University and Wu worked at Smith College. After a few years she accepted an offer from Princeton University as the first female instructor ever hired to join the faculty. In 1944, she joined the Manhattan Project at Columbia University where she helped answer a problem that physicist Enrico Fermi couldn't ascertain. She also discovered a way "to enrich uranium ore that produced large quantities of uranium as fuel for the bomb." In 1947 the couple welcomed a son, Vincent Wei-Cheng Yuan, to their family. Vincent would go on to follow in Wu’s footsteps and also became a nuclear scientist.

Nobel Prize Exclusion

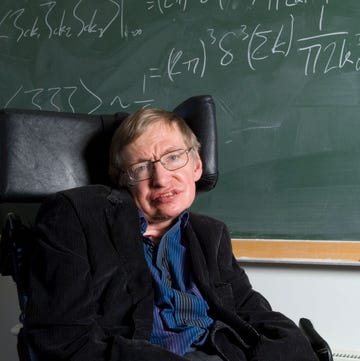

After leaving the Manhattan Project in 1945, Wu spent the rest of her career in the Department of Physics at Columbia as the undisputed leading experimentalist in beta decay and weak interaction physics. After being approached by two male theoretical physicists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, "Wu's experiments using cobalt-60, a radioactive form of the cobalt metal" disproved "the law of parity (the quantum mechanics law that held that two physical systems, such as atoms, are mirror images that behave in identical ways)." Unfortunately, although this led to a Nobel Prize for Yang and Lee in 1957, Wu was excluded, as were many other female scientists during this time. Wu was aware of gender-based injustice and at an MIT symposium in October of 1964, she stated "I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

Accomplishments and Awards

Wu was honored with many other accolades throughout her career. In 1958, she was the first woman to earn the Research Corporation Award and the seventh woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences. She also received the John Price Wetherill Medal of the Franklin Institute (1962), the National Academy of Sciences Cyrus B. Comstock Award in Physics (first woman to receive this award, 1964), the Bonner Prize (1975), the National Medal of Science (1975), and the Wolf Prize in Physics (inaugural award, 1978). She was the first woman to receive a Sc.D. from Princeton University (1958), and was awarded many honorary degrees.

In 1974 she was named Scientist of the Year by Industrial Research Magazine and in 1976, she was the first woman to serve as president of the American Physical Society. In 1990 the Chinese Academy of Sciences named Asteroid 2752 after her (she was the first living scientist to receive this honor) and five years later, Tsung-Dao Lee, Chen Ning Yang, Samuel C. C. Ting, and Yuan T. Lee founded the Wu Chien-Shiung Education Foundation in Taiwan for the purposes of providing scholarships to young aspiring scientists. In 1998 Wu was inducted into the American National Women’s Hall of Fame a year after her death.

Later Life and Legacy

After being promoted to Associate (1952) and then to Full Professor (1958) and becoming the first woman to hold a tenured faculty position in the physics department at Columbia, she was appointed the first Michael I. Pupin Professor of Physics in 1973. Her later research focused on the causes of sickle-cell anemia. Wu retired from Columbia in 1981 and devoted her time to educational programs in the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, and the United States. She was a huge advocate for promoting girls in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and lectured widely to support this cause becoming a role model for young women scientists everywhere.

Chien-Shiung Wu died from complications of a stroke on February 16, 1997 in New York City at the age of 84. Her cremated remains were buried on the grounds of Mingde Senior High School (a successor of Mingde Women's Vocational Continuing School). On June 1, 2002, a bronze statue of Wu was placed in the courtyard of Mingde High to commemorate her life.

Devoted to science, Wu mentored and encouraged not only her son, but dozens of graduate students throughout her career. She is remembered as a trailblazer in the scientific community and an inspirational role model. Her granddaughter, Jada Wu Hanjie, remarked “I was young when I saw my grandmother, but her modesty, rigorousness and beauty were rooted in my mind. My grandmother had emphasized much enthusiasm for national scientific development and education, which I really admire.”

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1912

- Birth date: May 31, 1912

- Birth Country: China

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Chinese-American nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, also known as "the First Lady of Physics,” contributed to the Manhattan Project and made history with an experiment that disproved the hypothetical law of conservation of parity.

- Industries

- Science and Medicine

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Schools

- University of California at Berkeley

- Cultural Associations

- Asian American

- Death Year: 1997

- Death date: February 16, 1997

- Death State: New York

- Death City: New York

- Death Country: United States

Fact Check

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right,contact us!

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Chien-Shiung Wu Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/chien-shiung-wu

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 17, 2021

- Original Published Date: June 1, 2016

QUOTES

- There is only one thing worse than coming home from the lab to a sink full of dirty dishes, and that is not going to the lab at all!

- … it is shameful that there are so few women in science… In China there are many, many women in physics. There is a misconception in America that women scientists are all dowdy spinsters. This is the fault of men. In Chinese society, a woman is valued for what she is, and men encourage her to accomplishments yet she remains eternally feminine.

- Beta decay was... like a dear old friend. There would always be a special place in my heart reserved especially for it.