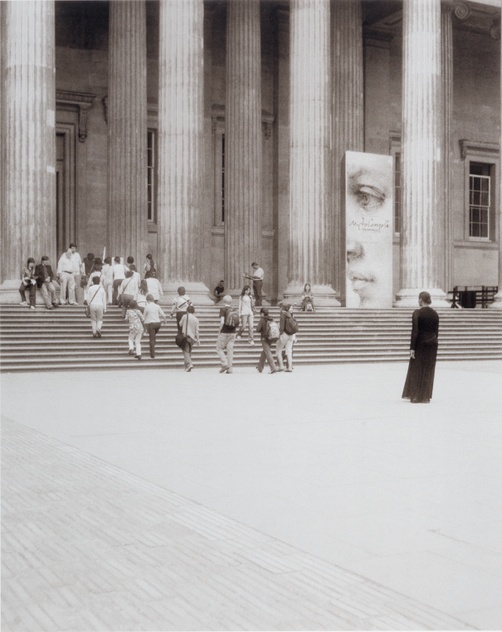

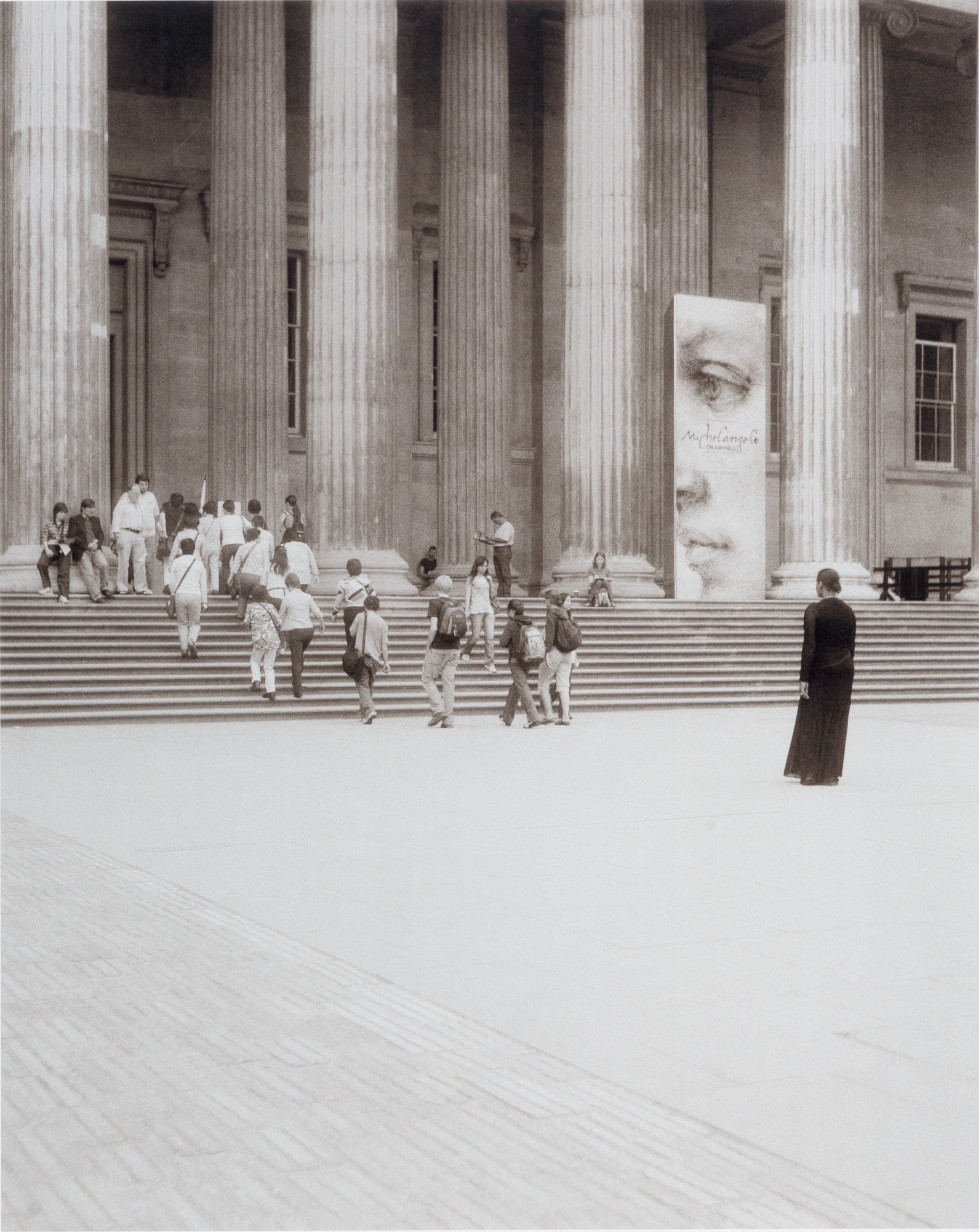

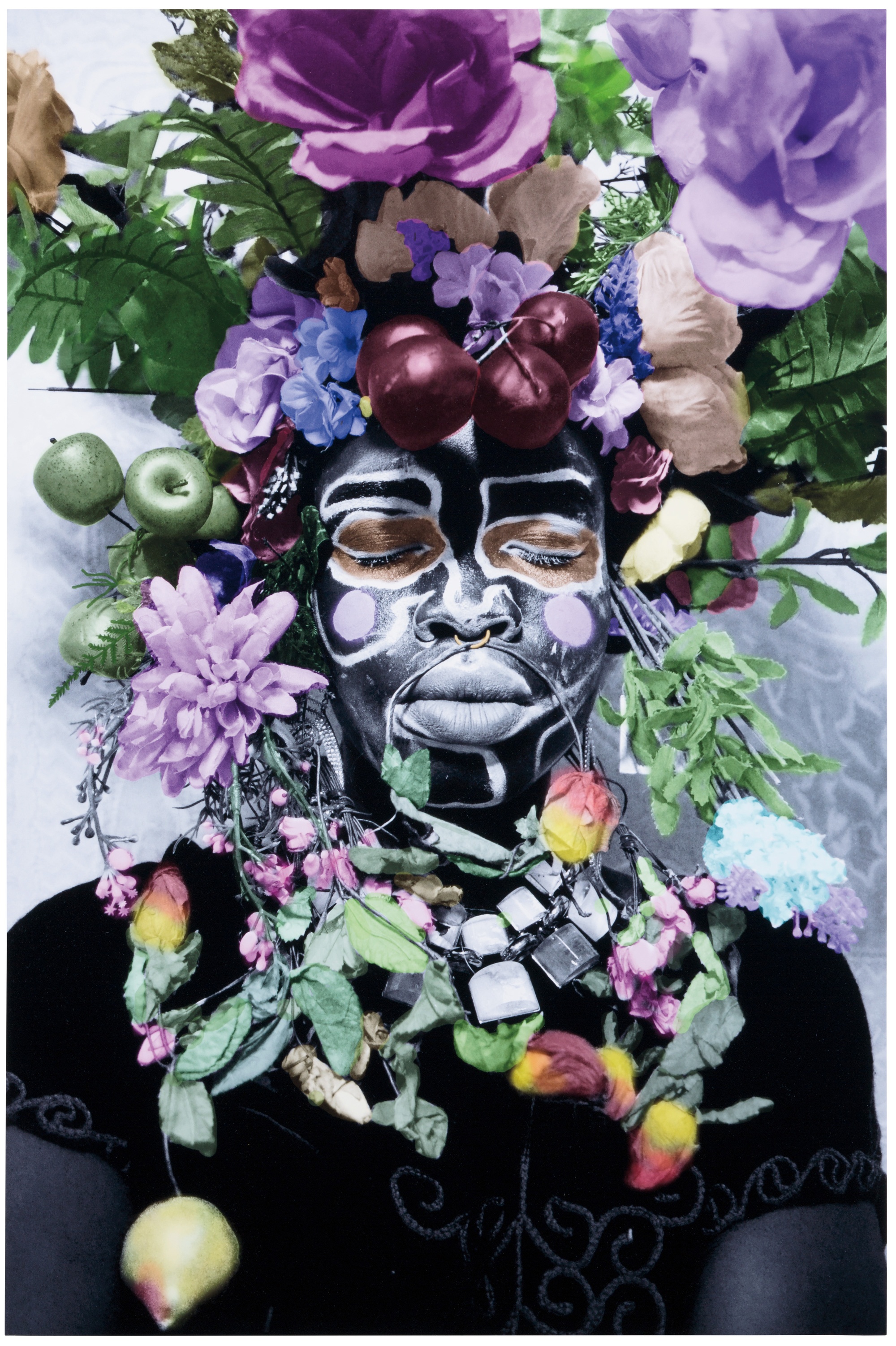

Carrie Mae Weems, When and Where I Enter the British Museum

Carrie Mae Weems, a contemporary American artist, places herself into the narratives of her photographs. When and Where I Enter the British Museum is part of a series of images taken outside some of the world’s most famous museums. In this series, Weems confronts the power dynamics of such institutions, imposed by the physical architecture, embedded social hierarchies, and class systems. Western museums, such as the British Museum, are often perceived as impartial collections of knowledge, despite being products of colonization, enslavement, and privilege. When museums do not acknowledge and address these histories of collection and display, they perpetuate a hegemonic narrative by reinforcing practices tied to imperialism. Weems challenges viewers to recognize whose stories are being told inside museums.

Weems, an African American woman, stands facing the British Museum, daring the institution to somehow confront and right its wrongs—regarding museum display, privilege, participation, belonging, and more. A banner showing the eye of one of Michelangelo’s statues, gazes toward the entrance of the British Museum, so that visitors enter under the gaze of a white male created by a revered white male artist. Do the large columns bar Weems from participation and belonging or is she refusing to enter under such conditions? Weems appears as a ghostly figure with her dark clothing and static posture: does her silhouette evoke the words of author Avery Gordon, by being “that which makes its mark by being there and not there at the same time”? With When and Where I Enter, viewers are asked to question how personal identity is shaped by institutions that often remain unquestioned and unchallenged. When and where have you felt prevented from feeling comfortable and expressing yourself?

—Chiara Garcia-Ugarte ’25 and Jae Hymer ’25