How Libraries Can Prepare for Natural Disasters and Preserve Community History

Beth Patin watched Hurricane Katrina wash her library away in 2005. Then a school librarian in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward, Patin saw more than a century of history at the school destroyed by the storm.

“It made me understand not just the value of libraries, but also the value of information that we have,” said Patin, an assistant professor at Syracuse University’s School of Information Studies. She said that while books are replaceable, historic artifacts and documents are “invaluable when it comes to collections.”

Libraries play many roles, including keepers of history for their communities by housing local newspaper archives or collections of town artifacts. Natural disasters and other emergencies threaten to erase community history if the libraries that house historical items are not adequately prepared.

There are steps that libraries serving small communities can take to prepare for such catastrophic events, and lessons individuals can learn from these institutions about protecting their own personal documents and keepsakes.

Libraries’ Role in Community Historic Preservation

Michele Farrell, a senior grants coordinator for the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), said she’s seen many small libraries across the United States function as historical societies for their towns. Typically, those librarians discuss with their boards which historical items they should collect and maintain and then decide whether the library has the space and expertise to maintain those items, she said.

“In some cases, the librarians have identified items from their collections that need to be digitized: papers on the founding of the town, school yearbooks, or pictures of farming equipment,” Farrell said in an email.

Newspaper archives were a key source for LaVerne Gray as she tracked down information about her grandmother’s fight to build a library for her Chicago public housing community, a process that became the subject of her dissertation.

She said the historical narratives that come from small and marginalized communities are invaluable and often overlooked.

“It’s like this underground, invisible web of these materials … that contain the communities’ narratives—historic or otherwise—and just pieces of life, which are really untapped in the academic sense,” said Gray, an assistant professor at Syracuse University’s School of Information Studies. “It’s not a part of the grand narrative.”

Those sorts of stories are fragile.

“Disasters impact … the unique collections owned by the library that tell the story of how a community came into being—information on all the various organizations, ethnic groups, natural resources, and businesses that were a part of it,” Farrell said in an email. “The community also loses a sense of pride because items lost might have reflected the diversity that used to exist in their area.”

Though libraries often play a role in historic preservation, it’s not always their priority. The risk to collections is higher for small institutions, which are generally less prepared for emergencies and less likely to focus on preservation, according to “Protecting America’s Collections,” a 2019 report from the IMLS. Compared with larger cultural institutions, smaller ones were less likely to prioritize assessing and preserving their digital collections, budgeting for preservation measures, developing formal preservation or emergency plans, or storing records of their collections off-site, according to the report.

Libraries are one player in historic preservation, and Farrell said it’s important for libraries to coordinate with other local organizations to help them evaluate how and where certain items are housed.

“What options does the library have to maintain a particular collection?” Farrell said. “By consulting with others, they can decide if they want to digitize themselves, send it out to be digitized, or donate the items to a

Of the nation’s collections, libraries contain:

92% of the nation’s books and bound volumes held for preservation

92% of photographic items

84% of recorded sound

70% of moving images

85% of unbound sheets (by volume)

Digitization has allowed institutions to preserve electronic records, images, catalog records, and other items. By volume, libraries contain 73% of the country’s digital collections, including most digital texts and geospatial files, according to the IMLS.

But changing digitization formats and standards can provide a challenge to creating electronic copies of documents and images, and digitization equipment and the experts who use it are limited.

Teamwork can help, Farrell said. In Massachusetts, for instance, the nonprofit Digital Commonwealth teamed up with the Boston Public Library to provide free digitization services for the state’s cultural organizations.

“You don’t want to be saving items that can readily be replaced or are housed at another institution,” she said. “It’s about having discussions with diverse members of your community, learning about what other institutions are doing regionally and on the state level, to better understand what you need to save and protect.”

By the Numbers: Damage and Loss at Cultural Institutions

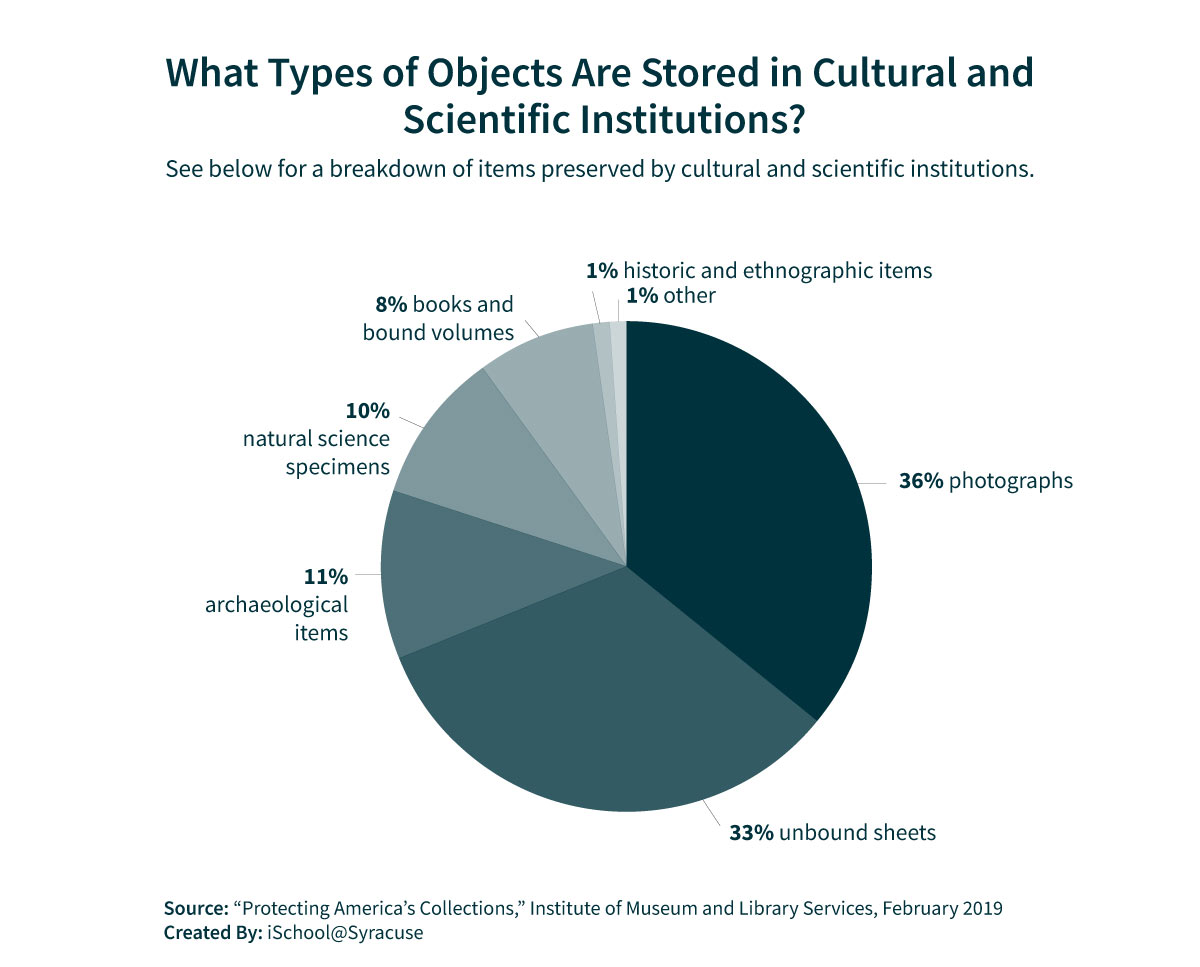

There are 13.2 billion items stored in U.S. libraries, museums, historical societies, archives, and scientific institutions, according to a 2019 report by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (PDF, 6.2 MB). They include historic, ethnographic, archaeological, natural science, and art objects; unbound sheets; photographs; recorded sound; and film.

Of the objects stored in cultural and scientific institutions, 36% are photographs, 33% are unbound sheets, 11% are archaeological items, 10% are natural science specimens, 8% are books and bound volumes, 1% are historic and ethnographic items, and 1% are other items.

Sources of Damage to Collections at Cultural Institutions

Damage to collections can originate from a variety of issues or events. This damage is exacerbated when 50 percent of libraries are citing improper storage or enclosure as a cause of the damage or loss.

RANDOM

- Fire: 2%

- Natural disaster: 10%

- Vandalism: 20%

HUMAN

- Prior conservation treatment/restoration: 7%

- Equipment obsolescence: 24%

- Handling: 44%

ENVIRONMENTAL

- Airborne particulates or pollutants: 15%

- Pests: 27%

- Light: 35%

- Physical/chemical deterioration: 41%

- Improper storage or enclosure: 45%

- Water/moisture: 56%

Preparing for and Protecting Against Natural Disasters

Planning for natural disasters is key for both individuals and cultural institutions.

California is among the states preparing their libraries for natural disasters, Farrell said. About 90 percent of institutions that attended disaster plan–writing workshops organized by the Pacific Library Partnership created complete disaster plans—a crucial undertaking as wildfires have ravaged towns across the state. At least 10 libraries and archives avoided or mitigated collection damage as a result of help they received from the partnership.

“They have helped many small libraries and museums extend the service lives of their collections by preparing plans, paying attention to security, managing their environment, and identifying items that need to be digitized,” Farrell said.

The steps libraries and other preservation organizations can take to protect their collections against natural disasters differ from those an individual would take.

When deciding whether to save or discard items at home, individuals might question whether an item brings them joy, as Marie Kondo suggests. However, library and museum professionals have to collaborate with other stakeholders and ask deeper questions about an item’s historical significance.

Disaster Preparedness Tips for Libraries

Libraries and historical preservation centers can implement these measures to help protect their collections against natural disasters:

CREATE AN EMERGENCY PLAN.

Write a comprehensive disaster plan and train your staff to execute the emergency response.

58% of libraries didn’t have written emergency or disaster plans for their collections;

18% had a plan but employees weren’t trained to carry it out;

24% of libraries had emergency plans and trained staff to carry them out, according to the IMLS.

USE THE CLOUD.

Store information on servers outside your building and use the cloud to back up vital information, such as collections lists, digital copies of materials, and contact information for staff members.

For digital preservation, Farrell suggested institutions use LOCKSS, an open-source software application.

34% of libraries had collections records stored off-site;

40% of libraries had collections records, but they were not stored off-site;

26% of libraries had no collections records, according to the IMLS.

BUILD RELATIONSHIPS WITH LOCAL EMERGENCY OFFICIALS.

Forge relationships with local government agencies and emergency planners and become familiar with local disaster plans beyond your walls. Library directors should also identify people they need to notify in case of an emergency, as well as emergency personnel and vendors they can work with during recovery.

If possible, library directors should be at the table when their community’s Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan (CEMP) is created. Such plans typically include disaster mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery measures.

“The library field has learned quite a bit since hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma hit,” Farrell said. “Now libraries are involved with the development of the CEMP plan.”

GET FAMILIAR WITH RECOVERY GRANTS AND OTHER RESOURCES.

Libraries are considered critical infrastructure and can receive FEMA funding and other resources to open temporary locations quickly after disasters. Local libraries can also seek support from their state libraries, which often offer continuing education related to disaster planning and are connected to other recovery resources.

PRACTICE SELF-CARE.

Communities rely on libraries for a range of services, such as free internet access, and the need for those services increases after disasters. Librarians need to take care of themselves in the wake of disasters so they can continue serving their communities.

“Traditionally libraries have focused on the idea of preserving the materials, which is critically important, but we lost sight of the value of our service,” Patin said.

Post-Katrina, Patin said she and other librarians went to work even when they were injured or going through their own grieving and recovery.

“We are going through trauma, and we’re processing trauma, and we’re helping other people process trauma,” Patin said. “It’s important for us to think about ourselves … as information first responders and make sure that we’re taking that time to check ourselves, check on our staff, and make sure that folks are having the kind of emotional and mental breaks that they need in order to continue to focus on service.”

*These tips were compiled based on suggestions from the IMLS, FEMA recommendations, and librarians’ personal experience.

Disaster Preparedness Tips for Individuals

Here are some ways you can protect your keepsakes and important documents:

INVENTORY THE IMPORTANT ITEMS IN YOUR HOUSE.

Create an inventory, documented with photos and videos of important items, documents, and valuables.

Disasters often make clear what we wish we had while we’re away from home. For Patin, it was pictures, art created by friends, and jewelry given to her by family members. Patin suggested keeping an empty Tupperware bin on hand with a laminated list of important items you would want to save on the lid.

“In a disaster, we can’t think straight,” Patin said. “Think about what is most important to you: What’s the most relevant thing for you to have to restart so that this next place feels like home?”

Documentation is also important when filing insurance claims.

MAKE DIGITAL AND PHYSICAL COPIES OF IMPORTANT DOCUMENTS.

Keep important documents in a safe place that can withstand fire and water, and protect your digital copies with strong passwords. Even if original marriage licenses, housing deeds, and insurance documents are stored in a lockbox at a bank, for example, they could be damaged if the bank is affected by a disaster. Having extra copies will provide some peace of mind and reduce difficulties if the originals are compromised.

CREATE A PLAN.

Follow ready.gov protocol to create a family emergency plan, and practice carrying it out. The website also suggests what to do when returning home after a disaster.

REVIEW YOUR INSURANCE AND OBTAIN A POLICY FOR SPECIFIC TYPES OF DISASTERS IF NECESSARY.

Standard homeowners’ insurance doesn’t typically cover damage from disasters like earthquakes, wildfires, and floods. If you live in an area with a higher risk for natural disasters, consider obtaining an insurance policy to cover specific types of damage.

STORE VALUABLES IN SAFE, DRY PLACES.

In earthquake zones, keep breakable items on low shelves. In flood zones, move valuables to higher levels.

KEEP CASH ON HAND.

It helps in the event banks and digital banking services are not accessible.

Recovery Resources

For more information on natural disaster preparedness and recovery for individuals, check out the following resources:

Additional information on natural disaster preparedness and recovery for libraries and other cultural institutions is available on these websites:

- American Library Association disaster preparedness and response guide

- ALA Preservation Week resources

- Institute of Museum and Library Services resource page

- Northeast Documentation Conservation Center’s dPlan disaster plan template

- Library of Congress preservation resources

- Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative

Citation for this content: Syracuse University’s online Master of Science in Library and Information Science program.