Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations

Fiscal Year 2024

A Message from the New York City Comptroller

Dear New Yorkers,

I am pleased to release my office’s Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations for FY 2023, part of our commitment to help ensure New York City’s long-term thriving by focusing on the soundness of our infrastructure and of our finances.

City capital dollars build the school buildings that educate our kids, the tunnels that bring us clean water, our public parks, libraries, and hospitals, affordable housing for families, the space and technology needed for our municipal government and courts, and the roads and bridges that New Yorkers rely on every day.

As our city grows and changes, so too do the needs and strains on our public realm. Aging infrastructure, population shifts, housing affordability, new technologies, and climate transition present challenges for the decades ahead.

While a modest portion of the funds to meet these needs come from the State and Federal governments, the vast majority comes through the City of New York’s municipal bond program, administered by the Comptroller’s Office and the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget.

This annual report focuses on the City’s capital debt: how much is outstanding, how much room we have to borrow for projects in the coming years, how much we can afford, and how we stack up compared to other U.S. cities. Some of the key findings:

- NYC currently has room to borrow under our State Constitutional debt limit (we are $37.2 billion below the limit of $131.6 billion). However, if we continue to commit capital at the rate projected in our capital plan, without faster growth of the debt limit, the City could exhaust its debt-incurring capacity by FY 2033.

- The percentage of tax revenues dedicated to debt service grew from 9.6 percent in FY 2022 to 10.2 percent in FY 2023, well below the 15 percent threshold used to evaluate affordability. However, we project that rising interest rates and greater capital debt will push that number up nearer to the threshold in the coming years.

- The City’s credit rating remains strong. NYC’s debt burden is relatively high compared to U.S. peer cities, but not unreasonably so when viewed in context. Rating agencies have maintained NYC’s bond rating at Aa2 (Moody’s), AA (S&P and Fitch), and AA+ (Kroll).

Simultaneously with the release of this report, my office is also establishing a new web-resource to help New Yorkers assess critical questions about NYC’s infrastructure. This new website will contain reports that look at:

- The state-of-good repair of our infrastructure (and the costs to achieve and maintain it).

- Vulnerabilities in the face of climate change.

- How we pay for the investments we need — including maximizing State and Federal dollars (like our recent report, Shifting Gears: Steering Federal Infrastructure Funds to Support NYC’s Transportation Future) as well as the analysis of debt affordability contained in this report.

- Efforts to address persistent delays and cost-overruns in our capital projects process.

- Economic development opportunities and policies to ensure that capital investments create good jobs for New Yorkers who need them.

One recent bright spot was the release of New York City’s new Capital Projects Tracker, which I’ve been fighting for now for over a decade — including sponsoring Local Law 37 of 2020 to require it — which was launched this fall by the Mayor’s Office of Operations. The Tracker will not only provide public transparency; it can also serve as a much-needed management tool to help drive reforms to get more projects built on-time and on-budget.

By attending to the soundness of both our public finances and our public infrastructure, we can help ensure a thriving future for New Yorkers for generations to come.

With an eye on the long term,

Brad

In accordance with New York City Charter §232, the Comptroller issues two reports annually on December 1st regarding the City’s capital debt and the status of capital projects.

This Report on Capital Debt and Obligations advises as to the maximum amount and nature of debt which, in the Comptroller’s opinion, the City may legally and soundly incur for capital projects during each of the four succeeding fiscal years. The report also provides an overview of the City’s debt outstanding and measures of debt burden.

The accompanying Report on the Status of Existing Capital Projects sets forth the amount of all obligations authorized for each pending capital project and the liabilities incurred for each project, by capital budget line. This file includes available funding for on-going capital projects and the total amount already expended since project inception.

The information appears in order by City Agency department code and includes the following:

-

- Appropriation Code: Unique identifier that describes, for each agency, the specific purpose for which funds were authorized in the capital budget for commitment and expenditure;

- Appropriation Name: Brief description of the specific purpose;

- Appropriated Amount: The total funds devoted to the specific purpose;

- Expended Amount: The amount of funds spent on the specific purpose;

- Encumbered Amount: The amount of funds designated to pay for the specific purpose, but not spent as of July 1st;

- Unobligated Amount: The funds currently available for spending for the specific purpose: Appropriated less Expended less Encumbered = Unobligated.

I. Executive Summary

The City of New York (the “City”) utilizes long-term debt to finance capital projects including its schools, water supply and sewers, affordable housing, transportation, public safety and justice facilities, parks, libraries, technology, and other infrastructure projects. The City can incur debt only up to a limit that is set in the New York State Constitution. In accordance with Section 232 of the City Charter, the City Comptroller is required to report the amount of debt the City may incur within the limit during the current fiscal year and each of the three succeeding fiscal years.[1] As in previous years, this report provides a comprehensive overview of the City’s debt, of its debt-incurring capacity, and affordability indicators, both over time and compared with a group of other U.S. cities.

Key Findings

- As of the start of FY 2024, the amount of outstanding City debt counted against the Constitutional limit[2] was $37.2 billion below the limit of $131.6 billion (i.e. debt-incurring capacity of 28.3 percent of the limit). Estimates as of the start of the fiscal year represent the high point of debt-incurring capacity.[3]

- The City’s indebtedness is projected to grow faster than the debt limit: the remaining debt-incurring power is forecast to drop to $27.7 billion below the limit of $152.5 billion projected by the start of FY 2027 (i.e. debt-incurring capacity of 18.1 percent of the limit). Table 1 below, drafted in accordance with Section 232 of the City Charter, provides the full projection.

- Based on the current projection of capital commitments,[4] should the debt limit (which is calculated via a formula based on the value of the city’s real property) slow its annual rate of growth to 3 percent starting in FY 2028, and assuming the City meets the targets of the published capital plan, the City would exhaust its debt-incurring capacity in FY 2033.

- The analysis of historical capital commitments included in this report suggests that the City will be able to meet and exceed the targets set by the FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan, which represents an improvement in the City’s efforts in recent years to accurately project and achieve Capital Commitment Plan targets.

- The share of tax revenues dedicated to debt service grew from 9.6 percent in FY 2022 to 10.2 percent in FY 2023, well below the 15 percent ceiling used to evaluate affordability as articulated in the City’s debt management policy. Based on current budget assumptions, the share is projected to reach 14.4 percent by FY 2033.

- NYC’s debt burden is relatively high compared to U.S. peer cities, but not unreasonably so when viewed in context. While debt per capita and relative to taxable value is well above the peer group average, debt outstanding as a percentage of personal income and debt burden as a percent of revenues is much closer to average. NYC should also be viewed as an essential leader of the global economy with economic strengths that flourish in a high-density environment, which drives the need for greater infrastructure and debt financing.[5]

- The City’s credit ratings remain strong. In fiscal year 2023, Moody’s Investors Service maintained the City’s GO bond rating at Aa2. Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings (S&P) maintained its rating of the City’s GO bonds at AA. Fitch Ratings (Fitch) upgraded its rating of GO bonds at AA. Kroll Bond Rating Agency (Kroll) rated the City’s GO bonds AA+.

Table 1. NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

| ($ in billions) | July 1, 2023 | July 1, 2024 | July 1, 2025 | July 1, 2026 |

| Gross Statutory Debt-Incurring Power a | $131.6 | $136.4 | $143.6 | $152.5 |

| Net Funded Debt Against the Limit | $69.4 | $74.9 | $82.2 | $90.1 |

| General Obligation (GO) Bonds Outstanding as of July 1, 2023 plus projected bond issuance (net) b | $40.0 | $42.3 | $45.5 | $49.1 |

| Less: Appropriations for GO Principal | ($2.5) | ($2.5) | ($2.4) | ($2.2) |

| Plus: Incremental TFA Bonds Outstanding Above $13.5 billion | $31.9 | $35.1 | $39.0 | $43.2 |

| Plus: Contract and Other Liability | $25.0 | $27.9 | $32.2 | $34.8 |

| Total Projected Indebtedness Against the Limit c | $94.4 | $102.9 | $114.4 | $124.9 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power within General Limit | $37.2 | $33.5 | $29.2 | $27.7 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power (%) | 28.3% | 24.6% | 20.4% | 18.1% |

Source: NYC Comptroller’s Office and the NYC Office of Management and Budget

Note: The Debt Affordability Statement released by OMB in April 2023 presents data for the last day of each fiscal year, June 30th, instead of the first day of each fiscal year, July 1, as reflected in this table. The City’s Debt Affordability Statement forecasts that indebtedness would be below the general debt limit by $22.71 billion at the end of FY 2024.

a See the appendix for a description of the methodology.

b Net adjusted for Original Issue Discount, GO bonds issued for the water and sewer system and Business Improvement District debt.

c Reflects City-funds capital commitments as of the FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan (released in September of 2023) and includes cost of issuance and certain Inter-Fund Agreements. In addition, the total indebtedness figure includes assumptions for future borrowing, estimated principal redemptions, and incremental changes to contract liability. In July 2009, the State Legislature authorized the issuance of TFA Future Tax Secured bonds above the cap of $13.5 billion, with the condition that this debt would be counted against the general debt limit. Thus, City capital commitments are funded with TFA debt as well as City GO bonds.

This report is organized as follows. Section II of this report contains an overview of the debt issued directly by the City or on behalf of the City through public benefit corporations or authorities.

Section III contains the estimates of the debt limit and remaining debt-incurring capacity. The methodology for this section was thoroughly revamped for this year’s report and the details are provided in the appendix. The updates focused on the estimation of the debt limit, with particular attention given to Special Equalization Ratios, which are crucial parameters provided by the New York State Office of Property Tax Services (ORPTS). The forecast of Special Equalization Ratios incorporates the empirical regularities and mechanical components implicit in the methodology used by ORPTS. In addition, this section incorporates risks and offsets to planned capital commitments. Finally, this section includes the estimate of debt-incurring capacity as of the end of the fiscal year (generally, its lowest point with the year) through FY 2033.

Section IV concludes the report with the analysis of debt affordability measures both for the City over time and across cities. This year’s report revises the selection of comparison cities and indicators as part of a forthcoming debt affordability study commissioned by the Office of the NYC Comptroller.

II. Profile of New York City Debt

Debt to support New York City’s capital program is issued directly by the City, or on its behalf, through a number of different debt issuing entities. This debt (gross NYC debt) is used to finance the City’s capital projects, and includes the City’s General Obligation (GO) bonds, all categories of NYC Transitional Finance Authority bonds (TFA), TSASC, Inc. bonds, and other conduit issuers included in the Capital Lease Obligations and other category (see Table 2).[6] While New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority (NYW) bonds also fund City capital projects, they are not included in gross NYC debt as they are paid for through charges for water and sewer service set and billed by the NYC Water Board.

In the 1980s, gross NYC debt grew at an average annual rate of 4.5 percent. During the 1990s, it increased by 6.4 percent annually. The substantial increase during the 1990s resulted mainly from the rehabilitation of facilities that were neglected during the 1970s fiscal crisis. Gross debt outstanding grew at a rate of 4.0 percent per year from FY 2000 to FY 2023. The June 2023 Financial Plan shows growth of approximately 6.8 percent annually through 2027.[7] Projections for growth rates may change as more detailed information about funding needs becomes available over time.

Composition of Debt

Excluding NYW bonds, the City issues two major types of debt to finance or refinance its capital program, with GO and TFA FTS bonds accounting for 40.9 and 46.6 percent of the outstanding debt total, respectively (Table 2). GO debt service is paid with Property Tax revenues from the General Debt Service Fund before remittance of the residual to the General Fund. TFA FTS debt service is paid from pledged revenues (Personal Income Tax and, if insufficient, the Sales Tax) before remittance of the residual to the General Fund. NYW debt service is paid for by water and sewer user fees. Table 2 contains information on General Fund supported debt.

Each of the categories of debt is comprised of both tax-exempt and taxable bonds, except for TSASC debt, which has been issued solely as tax-exempt bonds. Tax-exempt debt accounted for 80.1 percent of the total par amount of the City’s outstanding debt at the end of FY 2023. Taxable debt is issued for projects that have a public purpose but are ineligible for Federal tax exemption, such as housing loan programs.[8]

To diversify interest rate risk, gross NYC debt consists of both fixed and variable rate debt, with the bulk of the debt in fixed rate borrowing. At the end of FY 2023, fixed rate debt accounted for 91.5 percent of gross NYC bonds outstanding.

Table 2. Gross NYC Bonds Outstanding, June 30, 2023

| ($ in millions) | GO Bonds | TFA FTS | TFA BARBs | TSASC | Conduit Debt Issuersa | Gross Debt Outstanding | GASB 87 Capital Lease Obligationsb |

| Tax-Exempt | |||||||

| Fixed Rate | $26,916 | $31,964 | $7,041 | $938 | $3,302 | $70,161 | $0 |

| Variable | 5,100 c | 3,032 c | 0 | 0 | 156 | 8,288 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $32,016 | $34,996 | $7,041 | $938 | $3,458 | $78,449 | $0 |

| Taxable | |||||||

| Fixed Rate | $8,077 d | $10,631d | $838d | $0 | $0 | $19,546 | $12,963 |

| Variable Rate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $8,077 | $10,631 | $7,879 | $0 | $0 | $19,546 | $12,963 |

| Total | $40,093 | $45,627 | $7,879 | $938 | $3,458 | $97,995 e | $12,963 |

| Percent of Total | 40.9% | 46.6% | 8.0% | 1.0% | 3.5% | 100.0% | N/A |

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023

a This number includes $2.52 billion of Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) bonds and $21 million of tax lien securities, along with $918 million for five other conduit-debt issuers.

b Includes GASB 87 capital lease obligations of $12.96 billion that are reflected in the table to comply with accounting reporting requirements. There are no bonds associated with the figure shown above.

c Variable rate debt varies in term from two to 30 years, with interest rates that are reset on a daily, weekly, or other periodic basis.

d NYC GO taxable bond debt includes $2.43 billion of Build America Bonds and $22.14 million of Recovery Zone Economic Development Bonds. The TFA FTS taxable fixed rate debt includes $2.04 billion of Build America Bonds and $1.14 billion of Qualified School Construction Bonds. TFA BARBs taxable fixed rate debt includes $261 million of Build America Bonds and $200 million of Qualified School Construction Bonds.

e Total does not include impact of premiums/discounts on debt outstanding estimated at $7.13 billion in FY 2023.

General Obligation bonds and Transitional Finance Authority Future Tax Secured bonds above $13.5 billion are the only two forms of bonds included when calculating indebtedness under the general debt limit. Building Aid Revenue Bonds (BARBs), TSASC debt, and GASB 87 capital lease obligations and lease-purchase/conduit debt are not subject to the general debt limit.

General Obligation Debt

The use of GO debt, which is backed by the faith and credit of the City of New York, increased slightly in FY 2023 from FY 2022. As of June 30, 2023, GO debt totaled $40.09 billion and accounted for 40.9 percent of gross NYC debt outstanding, relatively unchanged from its share in FY 2022. GO debt outstanding includes Build America Bonds (“BABs”) and Recovery Zone Economic Development Bonds (“RZEDBs”). The FY 2023 GO debt total is $1.24 billion higher than GO debt outstanding at the end of FY 2022. During FY 2023, the City issued $6.16 billion of GO bonds, of which $3.91 billion were new money bonds for capital projects and $2.25 billion were GO refunding bonds. At the same time, the City redeemed 4.91 billion of its debt, including refunded bonds, during the fiscal year.

Debt service for GO bonds is paid from real property taxes which are deposited with and retained by the State Comptroller into the General Debt Service Fund under a statutory formula for the payment of debt service. This “lock-box” mechanism assures that debt service obligations are satisfied before property tax revenues are released to the City’s General Fund. NYC property tax revenues were $31.65 billion in FY 2023, more than four times FY 2023 debt service of $7.46 billion.[9]

Transitional Finance Authority Debt

The TFA issues two different types of debt — Future Tax Secured (FTS), backed primarily by the City’s personal income tax (PIT) revenues, and BARBs, supported by Building Aid paid by New York State. At the close of FY 2023, TFA debt totaled $53.51 billion, comprised of $45.63 billion of FTS debt and $7.88 billion of BARBs. This total is 3.3 percent greater than at the close of FY 2022.The TFA share of gross NYC debt outstanding decreased from 54.8 percent in FY 2022 to 54.6 percent in FY 2023. TFA issued $3.80 billion of TFA FTS new money bonds and about $2.70 billion of refunding bonds for TFA FTS and TFA BARBs combined during FY 2023 and had principal redemptions of $4.87 billion.

The TFA was created as a public benefit corporation in 1997 with the power and authorization to issue bonds up to an initial limit of $7.5 billion, but after several legislative changes the limit was increased to $13.5 billion. This borrowing does not count against the City’s general debt limit.[10] The City exhausted the $13.5 billion bonding limit in FY 2007. In July 2009, the State Legislature authorized TFA to issue debt beyond the $13.5 billion limit, with the additional borrowing subject to the City’s general debt limit. Thus, the incremental TFA debt issued in FY 2010 and beyond, to the extent the amount outstanding exceeds $13.5 billion, has been combined with City GO debt when calculating the City’s indebtedness within the debt limit.

Debt Not Subject to the General Debt Limit

In April 2006, the State Legislature authorized the TFA to issue up to $9.4 billion of outstanding BARBs. This debt is used to finance a portion of the City’s five-year educational facilities capital plan. BARBs are excluded from the calculation of the City’s debt counted against the debt limit. Between FY 2007 and FY 2009, $4.25 billion of BARBs were issued. Additional BARBs in the amount of $2.15 billion were issued over the FY 2011 – FY 2013 period followed by $1.5 billion in FY 2015, $750 million in FY 2016, $500 million in each of FYs 2018 and 2019, $250 million in FY 2020, and $200 million in FY 2021.[11] As a result of those debt issuances, excluding amortization through June 30, 2023, there are currently $7.88 billion of BARBs outstanding. In FY 2023, there was a TFA BARBs refunding transaction in the amount of $563.8 million, which generated gross budget savings of $73.6 million. Currently, there is no planned BARBs borrowing over FY 2024 – FY 2027. The Mayor, in concert with the New York City Comptroller’s Office, retains discretion with regard to the specific amount of annual BARBs borrowing.

In September of 2001, the State Legislature amended Chapter 16 of the Laws of 1997, to permit the TFA to have outstanding an additional $2.5 billion of its bonds and notes to pay for any and all expenses related to the terrorist attack on New York City on September 11, 2001. These “Recovery Bonds” are excluded from the debt limit. The Recovery Bonds are now fully retired as of June 30, 2023.

TSASC Inc. Debt

TSASC debt, which does not count toward the City’s general debt limit, totaled $938 million as of June 30, 2023. This represents about a $28 million decrease from FY 2022. There currently are no plans for future new money TSASC issuances. TSASC is a local development corporation created under and subject to the provisions of the Not-for-Profit Corporation Law of the State of New York. TSASC bonds are secured by tobacco settlement revenues (TSR) as described in the Master Settlement Agreement among 46 states, six jurisdictions, and the major tobacco companies. In January 2017, TSASC refinanced all bonds issued under the Amended and Restated 2006 Indenture. The refunding bond structure continues to allow the TSRs to flow to both TSASC and the City, with 37.4 percent of the TSRs pledged to TSASC bondholders, and the remainder going into the City’s General Fund.

Capital Lease (Conduit Debt) and Other Obligations (Excluded from Debt Limit Calculation)

Capital Lease and Other Obligations totaled $16.42 billion as of June 30, 2023, a decrease of $1.18 billion from FY 2022. The lower amount is driven by a decrease of $995 million in the GASB 87 capital lease calculation. However, the GASB 87 capital lease component still sums to a significant $12.96 billion as of June 30th, 2023, or 79 percent of the entire capital lease obligations and conduit debt category. The change in reporting policy beginning last fiscal year augmented the number of long-term capital leases eligible to be counted in the annual calculation to create greater transparency. There continues to be no practical impact on the City’s annual lease expenditures, which are not further burdened by the change in accounting reporting policy.

The City makes annual appropriations from its General Fund for agreements with other entities that issue debt to build or maintain facilities on behalf of the City. These agreements are known as “leaseback” transactions and result in a capital lease obligation. These capital lease obligations are shown as forms of indebtedness but are excluded in the calculation of the City’s indebtedness under the general debt limit. Capital lease obligations include debt issued by the DASNY for New York City Health + Hospitals (H+H) facilities ($344 million), the DASNY New York City Courts Capital Program ($221 million), the Educational Construction Fund ($290 million), the City University Construction Fund (CUCF) ($22 million)[12], the Industrial Development Agency ($52 million), the Primary Care Development Corporation ($11 million), as well as general lease obligations (GASB 87) ($12.96 million).[13] In addition, $21 million of NYC Tax Lien Trust debt was also included in this category.

The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) is a not-for-profit local development corporation formed in July 2004 to finance development in the Hudson Yards district of Manhattan — primarily the extension of the Number 7 subway line westward to 11th Avenue and 34th Street, which began operations in September 2015. As of June 30, 2023, HYIC had $2.52 billion in debt outstanding. No Interest Support Payments were made by the City to HYIC in FY 2023 nor are any planned for in the future. In August 2018, however, the City Council passed a resolution authorizing the issuance of up to $500 million in additional HYIC debt to fund Phase 2 of the Hudson Boulevard expansion and related park and infrastructure improvements from West 36th Street to West 39th Street in the Hudson Yards Financing district. HYIC has entered into a loan facility agreement with Bank of America, N.A. which provides $380 million of financing capacity, and as of June 30, 2023, the Corporation has drawn approximately $10.6 million of the loan facility.

Other Issuing Entities

In addition to the financing mechanisms cited above, a number of independent entities issue bonds to finance infrastructure projects in the City and throughout the metropolitan area. The two largest issuers are NY Water Financing authority (NYW) and the New York State Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Both entities have no statutory claim on revenues of the City of New York. Thus, the debt of NYW and MTA is not an obligation of the City. Nevertheless, bond proceeds from these entities are used to support capital projects that serve NYC residents. The outstanding indebtedness of these two authorities is summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

NYW had $32.25 billion in debt outstanding as of June 30, 2023, an increase of $711 million, or 2.3 percent, from FY 2022 as shown in Table 3. Debt issued by NYW is supported by fees and charges for the use of services provided by the system. Created by State law in 1984, NYW is responsible for funding the City’s water and sewer-related capital projects administered by the City’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), such as the construction, maintenance and repair of sewers, water mains, and water pollution control plants. Avoiding the need to build water filtration plants for upstate watersheds continues to be a high priority for DEP. Land acquisition strategies along with conservation-focused local development help the goal of preserving water quality. DEP’s FY 2024 – FY 2027 Four-Year Capital Program assumes an average annual cash funding need of $2.31 billion.[14]

The FY 2024 City-funds Adopted Capital Commitment Plan will continue to be a driver of water and sewer rate increases over the Financial Plan period. DEP’s current planned average annual authorized City-funds commitment level of $2.96 billion is 66 percent higher than the agency’s annual average actual capital commitments of $1.79 billion between FY 2021 and FY 2023. On average, the current DEP Capital Plan is about $155 million higher per fiscal year than its Capital Plan at this time last year.[15]

Table 3. NYW Debt Outstanding as of June 30, 2023

| ($ in millions) | Tax Exempt and Taxable |

| Fixed Rate | $27,310a |

| Variable Rate | 4,763 |

| Bond Anticipation Notes | 180 |

| Total | $32,253 |

Source: New York Water Finance Authority

a Includes $2.4 billion of Build America Bonds (Taxable)

The MTA, a State controlled authority, is composed of six major agencies providing transportation throughout the metropolitan area. The MTA is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the New York City Transit bus and subway system as well as the Long Island and Metro-North Railroads and various bridges and tunnels.

Debt issued to fund the MTA’s capital program is secured by several revenue sources: revenues from system operations, surplus MTA Bridges and Tunnels revenue, State and local government funding, and certain taxes imposed in the metropolitan commuter transportation mobility tax district, which includes the counties of New York, Bronx, Kings, Queens, Richmond, Rockland, Nassau, Suffolk, Orange, Putnam, Dutchess, and Westchester. In April 2019, the State enacted the MTA Reform and Traffic Mobility Act, which states that the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority needs to design, develop, build, and run the Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program (also known as Congestion Pricing). The CBD Tolling Program along with the 2019 Real Estate Transfer Tax and Internet Sales Taxes aim to provide a stable and recurring source of support to finance the MTA’s capital program needs. These initiatives are expected to fund approximately $25 billion of capital projects over the FY 2020 – FY 2024 Plan period and subsequent capital programs. The CBD Tolling Program, which is projected to generate $1 billion per year in revenue, and support $15 billion of funding for the MTA Capital Program, received federal approval earlier this year. Tolling operations could potentially begin in the first half of 2024.

As of June 30, 2023, as shown in Table 4, the MTA had $49.14 billion of debt outstanding, an increase of $1.32 billion, or 2.8 percent, from June 30, 2022. MTA debt has grown by 246 percent, or $34.95 billion since FY 2000. This growth rate is about 98 percentage points higher than the growth rate in gross NYC indebtedness over the same period.[16]

Table 4. MTA Debt Outstanding as of June 30, 2023

| ($ in millions) | Tax Exempt and Taxable |

| Fixed Rate | $46,020 |

| Variable Rate a | 3,118 a |

| Total | $49,138 |

Source: Metropolitan Transportation Authority. https://data.ny.gov/d/sze3-m8qh–

July 2023 in Excel Download

a Variable rate included $2.14 billion of synthetic-fixed bonds.

Note: $310 million of the above figure is classified as taxable debt.

Additionally, H+H has issued its own debt to fund capital improvements. These include the construction, renovation, improvement, and reconfiguration of H+H facilities and the acquisition and installation of machinery and equipment at H+H facilities. H+H debt is generally secured by all revenues, income, and receipts received by H+H, its providers, or HHC Capital with respect to the operation of the health system. A substantial portion of such monies are derived from Medicaid payments due to its providers. Of particular note, H+H bonds are secured by a reserve fund which, if unable to be replenished subsequent to a draw by H+H revenues, is to be replenished by City monies as certified by H+H to the City, subject to City appropriation. To date, the City has not been called upon to make such a payment. As of June 30, 2023, H+H had $479 million of bonds payable.

Analysis of Principal and Interest among the Major NYC Issuers

The two major types of debt that finance City capital projects outside the water and sewer system are NYC General Obligation and TFA FTS bonds. TSASC bonds [and TFA BARBs] are small components of debt outstanding and there is no additional planned new money debt issuance from either issuer. As a result, any new debt issuances will involve a mix of GO debt and TFA FTS bonds.

Table 5. Projected Combined NYC Debt Outstanding for GO, TFA, and TSASC, FY 2023 – FY 2033

| End of Fiscal Year | Debt Outstanding for GO, TFA, & TSASC ($ in millions) |

Percent Change in Debt Outstanding |

| 2023 | $94,537 | 3.2% |

| 2024 | $99,802 | 5.6% |

| 2025 | $106,703 | 6.9% |

| 2026 | $114,191 | 7.0% |

| 2027 | $122,045 | 6.9% |

| 2028 | $129,699 | 6.3% |

| 2029 | $137,074 | 5.7% |

| 2030 | $143,724 | 4.9% |

| 2031 | $149,175 | 3.8% |

| 2032 | $153,477 | 2.9% |

| 2033 | $156,793 | 2.2% |

Note: TFA figures include TFA BARBs. Future borrowing assumptions for FY 2024-2027 are from OMB’s Letter to the FCB, June 2023, Exhibit A-3 and for FY 2028-2033 the figures are from OMB’s April 2023 capital cash flow estimates.

Based on NYC Office of Management and Budget (OMB) forecasts, the debt outstanding is expected to grow at an annual average rate of 5.2 percent between FY 2023 to FY 2033, as shown in Table 5. However, the projected average annual growth rate in the first half of this period of 6.6 percent (FY 2023 – FY 2027) is higher than the rate for the period as a whole.[17] Average annual growth beyond the Financial Plan period (FY 2028 – FY 2033) is projected to drop to 3.9 percent, primarily because of the greater uncertainty of capital project specifics in the later years. Projections for this slower rate of growth are likely to change as more detailed plans are formulated.

The growth in debt outstanding is driven by the excess of borrowing over principal redemption. Borrowing is projected to average $11.52 billion annually according to OMB’s FY 2024 – FY 2033 capital cash flow estimates. This is an increase of about $600 million per year from the FY 2023 – FY 2032 capital cash flow estimates projected this time last year.[18] The combined principal and interest composition for GO, TFA and TSASC debt service is shown in Table 6.[19] The Financial Plan assumes principal payments totaling $4.17 billion in FY 2024, $4.18 billion in FY 2025, $4.39 billion in FY 2026, and $4.80 billion in FY 2027. Principal is estimated to be 54.2 percent of debt service in FY 2024, 51.0 percent in FY 2025, 49.0 percent in FY 2026 and 49.7 percent in FY 2027.[20]

Table 6. Estimated Principal and Interest Payments, GO, TFA FTS, and TSASC

($ in millions)

| Fiscal Year | Estimated Principal Amount | Estimated Interest | Estimated Total Debt Service | Principal as Percent of Total |

| 2024 | $4,168 | $3,527 | $7,695 | 54.2% |

| 2025 | $4,183 | $4,012 | $8,195 | 51.0% |

| 2026 | $4,388 | $4,569 | $8,957 | 49.0% |

| 2027 | $4,796 | $4,854 | $9,650 | 49.7% |

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget, FY 2024 Adopted Budget and June 2023 Financial Plan and Office of the NYC Comptroller.

Note: Adjusted for prepayments and excludes interest on short-term notes and debt service for capital lease / conduit debt. TFA BARBs debt is not included in this table.

During FY 2023, the City issued $6.16 billion of GO debt, $2.25 billion of which was for refunding purposes. These refunding issues produced gross budgetary savings of $145 million over the life of the bonds. The remaining amount of $3.92 billion was for new money purposes to finance capital projects. At the end of FY 2023, outstanding GO debt totaled $40.09 billion. Approximately $21.04 billion of the total GO debt currently outstanding (52.5 percent) will mature in the next ten years, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Amortization of Principal of the Three General Fund Issuers

($ in millions)

| Fiscal Years | GO | TFA | GO and TFA | Percent of Total | TSASC | Grand Total |

| 2024-2033 | $21,039 | $22,404 | $43,443 | 46.4% | $276 | $43,719 |

| 2034-2043 | $13,566 | $24,401 | $37,967 | 40.6% | $212 | $38,178 |

| 2044 and After | $5,488 | $6,701 | $12,189 | 13.0% | $450 | $12,640 |

| Total | $40,093 | $53,506 | $93,599 | 100.0% | $938 | $94,537 |

Note: numbers may not tie due to rounding.

A total of $5.93 billion of TFA FTS debt was issued in FY 2023, of which $3.80 billion was new debt to fund capital projects. The remaining $2.13 billion was used for refunding purposes, achieving $281 million of budgetary savings over the life of the debt. The TFA also issued refunding bonds for BARBs in the amount of $564 million to refund a portion of its debt at lower interest rates. Including BARBs, TFA’s debt outstanding was $53.51 billion at the end of FY 2023. Of the total TFA debt outstanding, $22.40 billion, or 41.9 percent, will come due over the next ten years, as shown in Table 7.

III. Debt-Incurring Power

This section of the report provides a description of the City’s general debt limit and estimates of its remaining debt-incurring power after the subtractions of indebtedness through FY 2027. In conformance with Section 232 of the NYC Charter, the Comptroller’s Office prepares a table (highlighted as Table 1 in the Executive Summary and Table 8 below) detailing the City’s debt-incurring power using the prescribed beginning-of-fiscal-year method. Within a fiscal year, this method results in the highest amount of debt-incurring power because it coincides with the timing of the appropriation of GO principal. For this reason, this section also provides estimates of debt-incurring power at the end of the fiscal year, which generally marks the low point of debt-incurring power within a fiscal year. The estimates are compared with NYC Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) statement of debt affordability which also estimates debt-incurring power as of the end of the fiscal year but is based on data from the Executive Financial Plan published in April 2023. The section ends with a projection of the City’s remaining debt margin through 2033.

The General Debt Limit

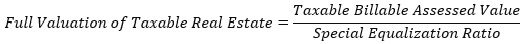

The New York State Constitution, Article VIII, sets limits to the amount of indebtedness of local governments (counties, cities, towns, villages, and school districts). Because, unlike New York City, local governments generally rely on the property tax as their main source of tax revenue, the value of the real estate within their jurisdictions represents a measure of the capacity to repay debt. Debt limits are set as a percentage of the five-year rolling average of the “full valuation of taxable real estate” (FV). In New York City, FV is derived from two sources: the City’s Department of Finance (DOF) Taxable Billable Assessed Value (TBAV) and the New York State Office of Real Property Tax Services (ORPTS) special equalization ratio. The formula is:

New York City’s general debt limit (also referred to here as debt-incurring power) equals 10 percent of the five-year rolling average of FV. Except for Nassau County, the other local governments in New York State have limits set at lower percentages.[21] In addition, because the debt limit does not take into account the City’s significantly more diversified tax revenue structure, the debt limit does not fully reflect the City’s ability to assume and service debt to finance infrastructure.

The New York City Council determines (“fixes”) the annual property tax rates upon approval of the City’s budget, pursuant to section 1516 of the City Charter. The so-called “tax fixing” resolution contains the calculations for the debt limit effective in the upcoming fiscal year. Table 8 contains the data for FY 2024.

Table 8. Calculation of the General Debt Limit, FY 2024

| Fiscal Year | Assessed Valuation of Taxable Real Property | Special Equalization Ratio | Full Valuation of Taxable Real Estate |

| 2020 | $257,509,634,870 | 0.2004 | $1,284,978,217,914 |

| 2021 | $271,688,749,747 | 0.2308 | $1,177,160,960,776 |

| 2022 | $257,560,316,555 | 0.2026 | $1,271,275,007,675 |

| 2023 | $275,614,595,502 | 0.2025 | $1,361,059,730,874 |

| 2024 | $287,719,502,079 | 0.1934 | $1,487,691,324,090 |

| 5Year Average Value | $1,316,433,048,266 | ||

| 10 Percent of the 5-Year Average | $131,643,304,827 | ||

Source: New York City Council Tax Fixing Resolution for FY 2024, p.5

Taxable Billable Assessed Value (TBAV)

TBAV is determined by the City’s Department of Finance (DOF) through the annual assessment process, which follows several steps, as determined by statute:[22]

- Classification of property into one of four classes.

- Estimation of DOF market value.

- Derivation of assessed values using assessment ratios.

- Derivation of TBAV by applying assessed value caps, phase-ins, and exemptions.

NYC’s DOF publishes a preliminary estimate of assessed values (“tentative assessment roll”) for the following fiscal year in January and a final estimate (“final assessment roll”) in May. The Office of the Comptroller’s forecast of TBAV is based on the FY 2024 final assessment roll and is consistent with the property tax revenue estimate published in Comments on NYC’s FY 2024 Adopted Budget. A description of the methodology is included in the appendix.

Special equalization ratio[23]

Under NYS Real Property Tax Law Article 12-A (sections 1250 through 1254), a special equalization ratio is required for cities with a population of 125,000 or more. As shown in Table 8, each year ORPTS publishes five ratios for the calculation of the debt limit. The ratios are based on the last completed assessment roll (e.g., for the FY 2024 limit, this is the FY 2023 assessment roll which is finalized in May 2022).

Statutorily, special equalization ratios are based on a market value survey. In 1996, section 1200 of the Real Property Tax Law was amended to authorize the use of real property sales data. However, as shown in the appendix, special equalization ratios bear a close relationship with equalization ratios derived from DOF market values. It should be noted, however, that DOF market values are roughly half of values compared with those derived from arms-length sales data, as shown by the Advisory Commission on Property Tax Reform.[24] Therefore, the special equalization ratios yield an underestimate of the true market value of NYC’s real estate.

Chart 1 shows the five-year average of equalization ratios starting in FY 1995. Other things being equal, higher ratios lower the debt limit and vice versa. Ratios fluctuated significantly in the past and their sharp increase in the mid-1990s necessitated the creation of additional financing capacity through the Transitional Finance Authority (TFA). However, since FY 2013 the 5-year average fluctuated in a relatively narrow range between 0.1947 and 0.2060. Equalization ratios are revised retroactively each year and their average was pushed up in FY 2023 by the revision of the FY 2021 ratio to 0.2307 (from the previous estimate of 0.2017). In FY 2026, when the FY 2021 ratio exits the five-year window, the average is projected to drop to 0.1961 and decrease to 0.1911 in FY 2027.

Chart 1. Five-year Average of Equalization Ratios

Source: NYS ORPTS, NYC Council Tax Fixing Resolutions, NYC Department of Finance, Office of the NYC Comptroller

Indebtedness

Pursuant to Section 135 of the NYS Local Finance Law, in general terms, indebtedness is defined as the sum of GO bonds, TFA Future Tax Secured bonds outstanding in excess of $13.5 billion, and capital commitments entered into but not financed with bond proceeds.[25] Indebtedness incurred by the NYC Water Authority or not funded by the City is excluded. The amount of indebtedness at the start of a fiscal year equals indebtedness at the end of the previous year minus appropriations for the repayment of GO principal. Therefore, as noted earlier, indebtedness at the start of the fiscal year is always lower than at its end.

The increase in indebtedness over the projection period is based on the Adopted Capital Commitment Plan for FY 2024-2027, however the details used in the estimate of the debt-incurring power are not published. Capital commitments are awarded contracts registered with the Office of the Comptroller. Commitments increase indebtedness irrespective of whether expenditures are incurred, or bonds are issued to fund capital projects. Commitments by the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) are excluded because they are funded by the NYC Water Authority.

Table 9 shows authorized commitments in the last four adopted plans. The table shows that in the current plan total authorized commitments dropped by $2.3 billion to $62.7 billion. The growth in total authorized commitments had already slowed to just $0.4 billion (0.6 percent) in the previous plan.

Table 9. Authorized Commitments, Net of DEP

| ($ in billions) Adopted Commitment Plan |

Authorized Commitments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | Total | |

| FY 2021-2024 | $12.8 | $13.7 | $14.2 | $15.5 | $56.2 | |||

| FY 2022-2025 | $17.8 | $17.5 | $15.3 | $13.9 | $64.6 | |||

| FY 2023-2026 | $18.6 | $18.8 | $15.3 | $12.3 | $65.0 | |||

| FY 2024-2027 | $18.7 | $16.8 | $13.7 | $13.5 | $62.7 | |||

Source: NYC OMB

In each year of the plan, the City sets a “reserve for unattained commitments,” which assumes that projects will move slower than reflected in the plan, and therefore some authorized commitments will be pushed outside the plan’s four-year window. The result is lower “target” commitment amounts. As shown in Table 10, target commitments in the current plan total $55.3 billion, a decline of $2.5 billion from the previous adopted plan. As in the previous three adopted plans, targets are backloaded.

Table 10. Target Commitments, Net of DEP

| Adopted Commitment Plan | Target Commitments ($ in billions) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY2021 | FY2022 | FY2023 | FY2024 | FY2025 | FY2026 | FY2027 | Total | |

| FY2021-2024 | $8.3 | $11.8 | $13.4 | $14.8 | $48.3 | |||

| FY2022-2025 | $11.6 | $15.4 | $15.4 | $14.4 | $56.8 | |||

| FY2023-2026 | $12.1 | $16.5 | $15.7 | $13.5 | $57.7 | |||

| FY2024-2027 | $12.1 | $15.2 | $14.2 | $13.8 | $55.3 | |||

Source: NYC OMB

Table 11 shows projected gross additions to indebtedness.[26] Gross additions are the target commitments over the projection horizon, plus other minor components (inter-fund agreements and the cost of bond issuance) as estimated by OMB. The gross additions to indebtedness total $57.2 billion by FY 2027. This is the amount that is factored in the estimate of the remaining debt-incurring margin.

The table also includes a projection of actual commitments based on historical trends, as detailed in the appendix. The trend analysis suggests that commitments could exceed targets by $2.4 billion over the length of the plan. The premium earned from bond sales is an offset to indebtedness that is also not included in the estimate of remaining debt-incurring margin.[27] As shown in the table, earning a 5 percent premium could generate additional margin of $2.3 billion by FY 2027. Overall, the risks and offsets to indebtedness in the FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitments Plan appear balanced.

Table 11. Projected Gross Additions to Indebtedness FY 2024 to

FY 2027

| ($ in billions) | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | Total |

| Target commitments (a) | $12.1 | $15.2 | $14.2 | $13.8 | $55.3 |

| Inter-fund agreements and cost of bond issuance (b) | $0.4 | $0.4 | $0.5 | $0.5 | $1.8 |

| Gross additions to indebtedness (c) = (a) + (b) | $12.5 | $15.6 | $14.7 | $14.2 | $57.1 |

| Projected variance of actual commitments (d) | $1.2 | -$1.1 | $0.6 | $1.8 | $2.4 |

| Assumed bond premium offset (e) | -$0.5 | -$0.6 | -$0.6 | -$0.7 | -$2.3 |

| Restated gross additions to indebtedness (c) + (d) + (e) | $13.2 | $13.9 | $14.6 | $15.4 | $57.2 |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

In the projection, target commitments are funded by the issuance of bonds in the amounts projected by OMB in the FY2024-2027 Financial Plan released in June 2023, the latest set of assumptions available at the time of writing. Commitments that are not yet funded by bond proceeds increase the contractual liability. Gross additions to indebtedness are partially offset by the repayment of principal over the projection period from the principal redemption schedules in OMB debt-service documents for GO and TFA along with schedules from NYC’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Report and TFA financial reports.

Remaining Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

Table 12 summarizes the projected change in the City’s debt-incurring power, as of the beginning of fiscal years 2024 through 2027, as required by the City Charter. The City’s FY 2024 general debt-incurring power of $131.6 billion is projected to increase to $136.4 billion in FY 2025, $143.6 billion in FY 2026 and $152.5 billion in FY 2027. The City’s indebtedness counted against the statutory debt limit is projected to grow from $94.4 billion at the beginning of FY 2024 to $124.9 billion by the beginning of FY 2027, leaving an estimated remaining margin of $27.7 billion by the end of the projection horizon.

Table 12. NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

| ($ in billions) | July 1, 2023 | July 1, 2024 | July 1, 2025 | July 1, 2026 |

| Gross Statutory Debt-Incurring Power a | $131.6 | $136.4 | $143.6 | $152.5 |

| Net Funded Debt Against the Limit | $69.4 | $74.9 | $82.2 | $90.1 |

| General Obligation (GO) Bonds Outstanding as of July 1, 2023 plus projected bond issuance (net) b | $40.0 | $42.3 | $45.5 | $49.1 |

| Appropriations for GO Principal | ($2.5) | ($2.5) | ($2.4) | ($2.2) |

| Incremental TFA Bonds Outstanding Above $13.5 billion | $31.9 | $35.1 | $39.0 | $43.2 |

| Contract and Other Liability | $25.0 | $27.9 | $32.2 | $34.8 |

| Total Projected Indebtedness Against the Limit c | $94.4 | $102.9 | $114.4 | $124.9 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power within General Limit | $37.2 | $33.5 | $29.2 | $27.7 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power (%) | 28.3% | 24.6% | 20.4% | 18.1% |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

Note: The Debt Affordability Statement released by OMB in April 2023 presents data for the last day of each fiscal year, June 30th, instead of the first day of each fiscal year, July 1, as reflected in this table. The City’s Debt Affordability Statement forecasts that indebtedness would be below the general debt limit by $22.71 billion at the end of FY 2024.

a See the appendix for a description of the methodology.

b Net of Original Issue Discount, GO bonds issued for the water and sewer system and Business Improvement District debt.

c Reflects City-funds capital commitments targets as of the FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan plus the cost of issuance and certain Inter-Fund Agreements. Total indebtedness includes assumptions of future borrowing from the FY 2024-2027 Financial Plan released on June 30, estimated principal redemptions, and incremental changes to contract liability. In July 2009, the State Legislature authorized the issuance of TFA Future Tax Secured bonds above the initial authorization of $13.5 billion, with the condition that this debt would be counted against the general debt limit.

The City’s remaining debt-incurring power, the difference between indebtedness (both contractual and funded by bond issuance) and the debt limit, is projected to decrease from $37.2 billion at the beginning of FY 2024 to $27.7 billion at the start of FY 2027. Over this period, the debt limit is projected to grow at an average annual growth rate of 5.0 percent, while total indebtedness against the limit is projected to grow at an annual rate of 7.2 percent. At the start of FY 2024, the remaining debt-incurring power was 28.3 percent of the debt limit, a percentage that is estimated to drop to 18.1 percent at the start of FY 2027.

Relative to the estimates published in 2022, the City’s gross statutory debt-incurring power in fiscal years 2025 and 2026 decreased by $0.3 billion and $2.0 billion, respectively as shown in Table 13. Total indebtedness is projected to remain below previous estimates by $4.3 billion at the start of FY 2025 and by $4.8 billion at the start of FY 2026. This is due to an overall reduction in commitments between the FY 2023 and FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitment Plans.

Table 13. Comparison of Debt-Incurring Power Estimates

| ($ in billions) | July 1, 2023 | July 1, 2024 | July 1, 2025 |

| Gross Statutory Debt Incurring Power | |||

| December 2022 Estimate | $131.7 | $136.7 | $145.6 |

| December 2023 Estimate | $131.6 | $136.4 | $143.6 |

| Difference | ($0.1) | ($0.3) | ($2.0) |

| Total Indebtedness Against the Limit | |||

| December 2022 Estimate | $94.4 | $107.2 | $119.2 |

| December 2023 Estimate | $94.4 | $102.9 | $114.4 |

| Difference | $0.0 | ($4.3) | ($4.8) |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power | |||

| December 2022 Estimate | $37.3 | $29.5 | $26.4 |

| December 2023 Estimate | $37.2 | $33.5 | $29.2 |

| Difference | ($0.1) | $4.0 | $2.8 |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller

At the beginning of a fiscal year, the remaining debt-incurring power reflects both changes in the debt limit and appropriations for GO principal. Over the course of the year, as capital contracts are entered into, the remaining debt-incurring power declines and reaches its minimum at the end of the fiscal year. Absent a decline in the debt limit, the remaining debt-incurring power increases at the beginning of the following year.

Remaining Debt-Incurring Power as of June 30th

Table 14 reports the estimate of debt-incurring power as of the end of the fiscal year through FY 2027. This is relevant because, as noted above, the debt limit is the lowest at the end of the fiscal year, and it is necessary to evaluate the difference with the debt affordability statement published in April of 2023 by OMB. The table shows that the remaining debt-incurring margin is expected to decline to $15.9 billion by FY 2027, or 10.5 percent of the projected general debt limit.

Table 14. NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of June 30th

| ($ in billions) | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 |

| General Debt Limit (a) | $127.4 | $131.6 | $136.4 | $143.6 | $152.5 |

| Debt Applicable to the Limit (b) | $71.9 | $77.4 | $84.5 | $92.3 | $100.6 |

| Net GO Bonds Outstanding | $40.0 | $42.3 | $45.5 | $49.1 | $53.2 |

| TFA Bonds above $13.5 billion | $31.9 | $35.1 | $39.0 | $43.2 | $47.4 |

| Less: Excluded Debt | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 |

| Contractual liability, land, and other liabilities (c) | $25.0 | $27.9 | $32.2 | $34.8 | $36.0 |

| Total Indebtedness (d) = (b) + (c) | $96.9 | $105.3 | $116.8 | $127.1 | $136.6 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power (a) – (d) | $30.5 | $26.3 | $19.6 | $16.5 | $15.9 |

| As a % of the General Debt Limit | 24.0% | 20.0% | 14.4% | 11.5% | 10.5% |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

As shown in Table 15, the remaining debt-incurring margin as of the end of the fiscal year is higher in the Comptroller’s estimate than in OMB’s latest debt affordability statement based on the Capital Commitment Plan released in April of 2023. In the updated Comptroller’s estimate, by FY 2027 the additional margin is $7.9 billion. The difference is mostly attributable to the decline of target commitments between the April and September plans: by FY 2027 the reduction totals $5.4 billion. Most of the residual difference ($2.4 billion) is due to a higher debt limit projection in FY 2027.

Table 15. Comparison of Comptroller and OMB Estimates

| ($ in billion) | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | |

| Debt limit | Comptroller | $131.6 | $136.4 | $143.6 | $152.5 |

| OMB | $131.3 | $135.7 | $143.4 | $150.1 | |

| Difference | $0.4 | $0.7 | $0.3 | $2.4 | |

| Debt applicable to the limit | Comptroller | $77.4 | $84.5 | $92.3 | $100.6 |

| OMB | $77.9 | $85.1 | $93.0 | $101.4 | |

| Difference | ($0.5) | ($0.6) | ($0.7) | ($0.8) | |

| Contractual liability, land, and other liabilities | Comptroller | $27.9 | $32.2 | $34.8 | $36.0 |

| OMB | $30.7 | $36.5 | $39.4 | $40.7 | |

| Difference | ($2.8) | ($4.2) | ($4.6) | ($4.8) | |

| Total indebtedness against the limit | Comptroller | $105.3 | $116.8 | $127.1 | $136.6 |

| OMB | $108.6 | $121.6 | $132.4 | $142.1 | |

| Difference | ($3.3) | ($4.8) | ($5.3) | ($5.5) | |

| Of which: targets revision April to September (cumulative) | ($4.2) | ($5.3) | ($5.5) | ($5.4) | |

| Remaining debt-incurring power | Comptroller | $26.3 | $19.6 | $16.5 | $15.9 |

| OMB | $22.7 | $14.2 | $11.0 | $8.0 | |

| Difference | $3.6 | $5.5 | $5.6 | $7.9 |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

Table 16 combines beginning- and end-of-FY estimates to show how the remaining debt-incurring margin is depleted through the year by the issuance of debt and new contractual commitments that remain unfunded. For instance, in FY 2024 the remaining debt-incurring power started at $37.2 billion and is projected to drop by $10.9 billion by June 30. Additional margin is created at the beginning of FY 2025 by the increase of the debt limit from $131.6 billion to $136.4 billion, and by the appropriation of funds for the reimbursement of GO principal (the full amount of the appropriation reduces outstanding debt on July 1). Therefore, the remaining debt-incurring power is expected to end FY 2024 at $26.3 billion and to start FY 2025 at $33.5 billion. In the projection, the increases in debt-incurring power at the beginning of the fiscal years are smaller than the additional indebtedness within each year. Therefore, the remaining debt-incurring power drops from FY 2024 to FY 2027.

Table 16. Comparison of Beginning- and End-of-FY Estimates

| FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | |||||||||

| ($ in billions) | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change |

| Debt limit | $131.6 | $131.6 | $0.0 | $136.4 | $136.4 | $0.0 | $143.6 | $143.6 | $0.0 | $152.5 | $152.5 | $0.0 |

| Debt | $69.4 | $77.4 | $8.0 | $74.9 | $84.5 | $9.6 | $82.2 | $92.3 | $10.1 | $90.1 | $100.6 | $10.5 |

| Contracts not funded | $25.0 | $27.9 | $2.9 | $27.9 | $32.2 | $4.3 | $32.2 | $34.8 | $2.6 | $34.8 | $36.0 | $1.2 |

| Remaining debt-incurring power | $37.2 | $26.3 | ($10.9) | $33.5 | $19.6 | ($13.9) | $29.2 | $16.5 | ($12.7) | $27.7 | $15.9 | ($11.7) |

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

Finally, Chart 2 shows a projection of the debt-incurring margin as of the end of the fiscal year, through FY 2033. In this exercise, the debt limit is assumed to grow at a yearly rate of 3.0 percent. This rate is half of the average annual growth rate established between FY 2004 and FY 2024 (6.1 percent), and slightly above the 2.3 percent annual rate since FY 2021. Target commitments and debt issuance assumptions to FY 2033 are projections from OMB. The chart shows that, under these assumptions, the achievement of target commitments as currently planned would exhaust the debt-incurring margin in FY 2033. The estimates do not factor in offsets from the issuance of premium bonds nor the City’s capacity to issue debt that is not counted toward the limit through various entities, both of which alleviate the erosion of the remaining debt-incurring power. On the other hand, future additions to capital commitment targets, assuming the City establishes the capacity to achieve them consistently, would accelerate its depletion.

Chart 2. Ten-Year Projection of Debt-Incurring Margin as of June 30th

($ in billions)

Source: Office of the NYC Comptroller, NYC OMB

IV. Debt Burden and Affordability of NYC Debt

This section presents measures to assess the size of the City’s debt burden and its affordability. No single measure completely captures debt affordability; hence we employ several measures that can be used to assess a locality’s debt burden. This section provides measures of debt per capita, debt as a percent of the value of real property, debt as a percent of personal income, and debt-service as a percent of local tax revenues and total expenditures. For three of these measures, comparisons with other jurisdictions are presented.

Background

The Capital Commitment Plan published by NYC OMB is a compilation of estimated future contract registrations for all the City’s new construction, physical improvements and equipment purchases that meet capital eligibility requirements. About 25 agencies engage in some form of capital work, with 14 agencies accounting for approximately 95 percent of planned capital commitments. This planning document serves as the foundation for the registration of contracts from which future capital expenditures occur. A capital commitment refers to a contract registration and does not represent a capital expenditure. Capital expenditures occur after a contract is registered, and the related spending against that contract can last several years. Capital expenditures are initially paid out of the General Fund. The financing of capital projects takes place after spending occurs to reimburse the City’s General Fund. GO and TFA bonds finance all City agencies’ capital projects, with the exception of DEP projects, which are financed by the NYW. In addition, the City does not finance individual projects in isolation, but rather finances portions of multiple projects simultaneously with each bond issuance.

The City-funded share of the FY 2024 Adopted Commitment Plan’s authorized commitments over FY 2024 – FY 2027 totals $74.55 billion, about the same as at this time last year. Non-City funding comes from state, federal, and private grants and accounts for only 4.3 percent of the total capital plan. City-funded commitments, after adjusting for the reserve for unattained commitments of $8.95 billion, total $65.60 billion.[28] Five programmatic areas comprise 77.0 percent of the City-funded plan, as shown in Chart 3. Housing and Economic Development related capital projects comprise 18.8 percent of the four-year plan, followed by the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) at 15.9 percent, Education (DOE)/City University of New York (CUNY)at 14.6 percent, the Administration of Justice related projects (Correction, Police, and Courts) at 14.1 percent, and the Department of Transportation (DOT) and Mass Transit at 13.6 percent. Combined, these five areas account for $57.38 billion of the $74.55 billion authorized City-funds plan.

Chart 3. Allocation of $74.6 Billion City-Funds Capital Commitments FY 2024 Adopted Four-Year Commitment Plan

($ in millions)

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget, FY 2024 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan, published September 2023

The FY 2024 Adopted City-funds Capital Commitment Plan, after the reserve for unattained commitments, projects an average of $16.40 billion per year in City-funded commitments over FY 2024 – FY 2027. This represents a decrease of over $450 million from the annual average in last year’s Adopted Commitment City-funds Plan of $16.87 billion. The Commitment Plan forecast is not front-loaded, with approximately 22 percent of the commitments of the current four-year Plan scheduled in FY 2024.[29]

The City’s capital program is financed almost exclusively by the issuance of bonds, which are repaid out of the City’s expense budget in the form of debt service payments. The City’s annual borrowing, excluding NYW debt, grew from $3.53 billion in FY 2000 to $7.72 billion in FY 2023, with the highest annual borrowing of $7.75 billion still occurring in FY 2009, as shown on Chart 4. OMB expects the City’s borrowing to average $11.5 billion annually between FY 2024 through FY 2027, with a peak estimated borrowing of $13.1 billion in FY 2028.[30] The $11.5 billion average over the four-year period is about the same as this time last year.[31] This level of borrowing, if fully executed, will put increased pressure on the operating budget in the event tax revenues are lower and do not meet the Financial Plan’s expectations. In addition, there would be cautionary pressure on the City’s general debt limit after the FY 2024 – FY 2027 Financial Plan period.

The annual average growth rate of City debt service payments between FY 2000 and FY 2023 was 4.1 percent per year, growing from $3.0 billion in FY 2000 to $7.38 billion in FY 2023.[32] According to OMB projections, the City’s debt service is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 6.6 percent from FY 2024 to FY 2033, or to $13.6 billion by FY 2033, as illustrated in Chart 4. Projected growth during the four years of the Financial Plan period is 7.9 percent per annum, more than the projected average annual growth rate of 5.4 percent in FY 2028 – FY 2033. However, the rate of growth over the Financial Plan period (FY 2024– FY 2027) will likely be lower as the projection incorporates fairly conservative long-term bond interest rate assumptions and does not take into account the likelihood of refunding actions and lower than projected capital commitment (contract registration) rates. Conversely, the growth estimate beyond FY 2027 is low and might be higher than the projected pace largely because of rollovers from prior years to later years; as the timeframe approaches for those latter years, more accurate estimates are produced.

Chart 4. Bond Issuance and Debt Service, FY 2000 – FY 2033

($ in millions)

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports Office of the NYC Comptroller, 2000 – 2023. Debt-service payments exclude interest on short-term notes, Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC) debt, BARBs debt and lease-purchase debt and are adjusted for budget surpluses prepaid to the debt-service fund. However, BARBs are included in bond issuance. The outyear forecasts for FY 2024-2027 were from Exhibit A-3 of the OMB Letter to the FCB, June 2023. FY 2028 through FY 2033 were from OMB’s capital cash flow document, April 2023.

Note: FY 2000 – FY 2023 are actuals. FY 2024- FY 2033 are estimated.

Debt Burden

NYC debt outstanding has increased from $39.55 billion to $98.0 billion, or 148 percent, over FY 2000 – FY 2023.[33] Over this same period, the growth in NYC personal income was at 138 percent, with growth in NYC local tax revenues at 227 percent and the City-funds expense budget at 216 percent.[34] (The debt outstanding figures do not include the debt of the NYW and the MTA.)

Debt Outstanding as a Percent of Personal Income, FY 1970 – FY 2027

In the early 1970s, the City issued short-term notes which it did not entirely redeem at the end of each fiscal year. From 1970 to 1975, the City’s year-end short-term note balance averaged $2.77 billion, with $4.44 billion outstanding at the end of FY 1975. This signal of financial stress contributed to the City’s inability to access credit markets and the eventual involvement of the State and Federal governments beginning in March 1975. Confronted with external controls in the aftermath of the fiscal crisis, the City rapidly reduced its indebtedness in the late 1970s. This, combined with the resurgence of Wall Street in the 1980s, resulted in the decline of the ratio of debt to personal income from 1976 to 1990.

Chart 5 illustrates the historical and projected trend of gross debt outstanding as a percentage of personal income from FY 1970 to FY 2027. After reaching a peak of 25.6 percent in FY 1976, gross debt as a percent of NYC personal income trended downward, reaching a low of 12.5 percent in FY 1989. Through the 1990s, the ratio averaged 14.2 percent before rising to 16.6 percent in FY 2005 in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Between FY 2006 and FY 2021, the ratio averaged 16.1 percent. In FY 2022, the ratio was 13.7 percent and is estimated to be 14.7 percent in FY 2023 before reaching 16.1 percent by FY 2027.[35]

Chart 5. NYC Gross Debt as a Percent of Personal Income, FY 1970 – FY 2027

Sources: Office of the NYC Comptroller, Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports for the Fiscal Years ended June 30, 1990, 1999, 2010 and 2023. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, FY 2022 personal income for counties and the NYC Office of Comptroller for FY 2023-FY2027 personal income estimates. Gross Debt Outstanding figures used here are at par value.

Note: Actual figures are in FY 1970 – FY 2022. Projected figures are in FY 2023 – FY 2027.

NYC Debt Outstanding as a Percent of Assessed Value of Taxable Real Property

Over the period from FY 2000 – FY 2011, the ratio of debt outstanding to taxable assessed value of real property averaged 45.2 percent. The average ratio dropped to 38.9 percent over FY 2011 – FY 2022. This ratio declined in each fiscal year over this period from 46.1 percent in FY 2011 to 36.6 percent in FY 2022, but has now further decreased to 34.5 percent in FY 2023, as shown in Chart 6. This ratio is projected to remain flat at 34.5 percent in FY 2024, and continue to rise over the period, reaching an estimated 37.7 percent in FY 2027, driven by a disparity in growth between taxable assessed value and debt outstanding. Taxable assessed value is projected to grow by 3.5 percent annually from FY 2024 – FY 2027 compared to a projected 6.6 percent annual growth in debt outstanding.[36]

Chart 6. NYC Outstanding Debt as a Percentage of the Assessed Value of Taxable Real Property

($ in billions)

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the Comptroller and NYC Department of Finance, FY 2023 Annual Report of the NYC Real Property Tax, NYC Dept. of Finance. Growth estimates for FY 2024 to FY 2027 by NYC Comptroller’s Office

Note: FY 2000- FY 2023 are actuals. FY 2024 – FY 2027 are projected

NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Tax Revenues

Another measure of debt affordability is annual debt service expressed as a percent of annual local tax revenues. This measure shows the pressure that debt service exerts on a municipality’s locally generated revenues. Debt service exceeded 15 percent of tax revenues – a threshold frequently identified by oversight entities and rating agencies as a prudent limit – in 8 of the 11 years from FY 1992 to FY 2002, with a peak of 17.2 percent in FY 2002.[37] Since then, this ratio has trended downward, reaching 9.6 percent in FY 2022 and 10.2 in FY 2023, as shown in Chart 7. Debt service as a percentage of tax revenues is projected to reach a high of 12.6 percent in FY 2027. This is driven by estimated debt service growth of 7.8 percent per year over the FY 2024 – FY 2027 Financial Plan period compared to 2.6 percent annual growth for local tax revenues.[38] This debt service growth is due both to higher levels of anticipated future borrowing and conservatively budgeted interest rates.

Chart 7. NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Tax Revenues

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the Comptroller, FY 2000 – FY 2023, and NYC Office of Management and Budget, FY 2024 Adopted Budget, June 2023 Financial Plan

Note: FY 2000-FY 2023 are actuals. FY 2024 – FY 2033 are projected

Debt service as a percent of total revenues ranged from 6.3 percent to 9.6 percent over FY 2000 – FY 2023, as shown in Chart 8. Over this period, this ratio averaged 7.8 percent, with a median of 7.7 percent. The ratio is forecast to reach 9.0 percent in FY 2027 due to a projected average annual growth rate of debt service exceeding the estimated average annual growth rate of total revenues by a margin of over seven percentage points, 7.7 percent versus 0.5 percent, respectively, from FY 2024 to FY 2027.[39]

Chart 8. NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Total Revenues

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the Comptroller, FY 2000 – FY 2023, and NYC Office of Management and Budget June 2023 Financial Plan

Note: FY 2000 – FY 2023 are actuals. FY 2024 – FY 2027 are projected

While New York City has a large amount of outstanding debt, its credit rating remains strong, as shown in Table 17. In Fiscal Year 2022, Moody’s Investors Service maintained the City’s GO bond rating at Aa2. Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings (S&P) maintained its rating of the City’s GO bonds at AA. Fitch Ratings (Fitch) upgraded its rating of GO bonds to AA. In Fiscal Year 2022, the City’s GO bonds received a rating of AA+ from Kroll Bond Rating Agency (Kroll). Rating agencies cite the City’s large and diverse economy, strong financial management, and liquidity among positive credit attributes that support GO ratings. High TFA and NYW ratings reflect their strong legal frameworks and debt service coverage by pledged revenues.

Table 17. Ratings of Major New York City Debt

| Rating Agency | GO | TFA Future Tax Secured (FTS) Senior | TFA FTS Subordinate | TFA BARBs | NYW First Resolution |

NYW Second Resolution |

| S&P | AA | AAA | AAA | AA | AAA | AA+ |

| Moody’s | Aa2 | Aaa | Aa1 | Aa2 | Aa1 | Aa1 |

| Fitch | AA | AAA | AAA | AA | AA+ | AA+ |

| Kroll | AA+ | Not Rated | Not Rated | Not Rated | Not Rated | Not Rated |

Comparison with Selected Municipalities[40]

New York City is the largest city in the U.S., with a population over twice as large as that of second ranked Los Angeles, and a complex, varied, and aging infrastructure. The city has more school buildings, firehouses, health facilities, community colleges, roads and bridges, libraries, and police precincts than any other city in the nation. Moreover, NYC has broader responsibilities than the majority of other large cities in the U.S. These responsibilities include city, county, and school district functions and, as a result, NYC has similarities to many county governments. Responsibilities for various functions in other large U.S. cities generally are distributed broadly to state, county, school districts, public improvement districts, and public authority governmental units. NYC has responsibility for all of these functions.

Selection of the Peer Group

NYC has important features that pose challenges when attempting to identify peers among other U.S. cities and in drawing useful comparisons. One of these is its sheer scale and density, including population, infrastructure, and economic activity relative to other large U.S. cities. The other feature to consider is NYC government’s broad scope of responsibilities, an important difference that distinguishes itself from virtually all of its potential peers. Therefore, when selecting an appropriate peer group for the City, it is important to consider both scale and governance. Differences in scale and governance can be partially mitigated with ratio analysis, similar to the efforts of rating agencies, and by using, where appropriate, Direct and Overlapping Debt, in order to address differences in governance structure, when measuring debt burden and debt affordability. As discussed in more detail below, Direct and Overlapping debt includes not only the debt of the peer city, but also other debt (for example, issued by school districts) supported by taxpayers in that jurisdiction.

The Peer Group includes the top 10 most populous U.S. cities, representing different regions and a variety of infrastructure life cycles, and then expanded by adding cities that were both highly ranked in population (that is, ranking at least among the top 25 nationally) and which also assumed city and county functions along with direct responsibility for funding and financing their schools.

While NYC may have more in common with other international financial and commercial centers, such as London, Paris, Shanghai, Seoul, Tokyo and others in terms of population and level of business and cultural vibrancy, these were not considered for inclusion in the Peer Group because of the lack of direct comparability in terms of legal structure, funding sources, budgeting, accounting and financing practices.

The Peer Group is shown in Table 18, along with each city’s credit ratings, population, and governing functions and responsibilities.

Table 18. New York City Peer Group Identified for Comparisons

| Population | City & County Functions | GO School Funding & Borrowing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Moody’s | S&P | Fitch | Kroll | Total | National Rank | ||

| New York City | Aa2 | AA | AA | AA+ | 8,467,513 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| Los Angeles | Aa2 | AA | AAA | AA+ | 3,853,323 | 2 | No | No |

| Chicago | Baa3 | BBB+ | BBB+ | A | 2,746,388 | 3 | No | No |

| Houston | Aa3 | AA | AA | – | 2,300,027 | 4 | No | No |

| Phoenix | Aa1 | AAA | AAA | – | 1,630,195 | 5 | No | No |

| Philadelphia | A1 | A | A | – | 1,576,251 | 6 | Yes | No |

| San Antonio | Aaa | AAA | AA+ | – | 1,451,863 | 7 | No | No |

| San Diego | Aa2 | AA | AA | – | 1,411,034 | 8 | No | No |

| Dallas | A1 | AA | – | – | 1,304,379 | 9 | No | No |

| Austin | – | AAA | AA+ | – | 975,321 | 10 | No | No |

| San Francisco | Aaa | AAA | AA+ | – | 815,201 | 17 | Yes | No |

| Nashville | Aa2 | AA+ | – | AA+ | 715,884 | 21 | Yes | Yes |

| Washington DC | Aaa | AA+ | AA+ | – | 667,837 | 23 | Yes | Yes |

| Boston | Aaa | AAA | – | – | 654,776 | 25 | Yes* | Yes |

* Formerly consolidated with Suffolk County, MA; county government abolished in 1999.

Source: Population as of 2021; derived from FY 2022 ACFRs of each city. Ratings sourced from publicly available credit reports as of September 27, 2023

Metrics Selected for Comparison between NYC and the Peer Group

The Peer Group metrics provided herein utilize data and calculations from each Peer Group member’s Annual Comprehensive Finance Report (ACFR). Although some of the nuances specific to each city are difficult to conform, the ACFRs provide the most comparable and readily available data. Additionally, when comparing debt metrics between jurisdictions, it is important to obtain the data from uniform sources, wherever possible. Using the table of Direct and Overlapping Debt from each Peer Group member’s ACFR ensures greater comparability because this table provides the total amount of GO and other property tax levy supported debt obligations that are imposed upon the taxpayers of each Peer Group member, regardless of governance structure. For example, if the Peer Group comparisons utilized Direct Debt rather than Direct and Overlapping Debt, the Chicago Board of Education’s debt would be excluded from Chicago’s calculations since it is a separate entity from City of Chicago and finances its own capital program. As a result, comparability between Chicago and NYC would be reduced because NYC directly finances the capital program for NYC Public Schools, the largest school district in the nation, which is an integral part of the City’s reporting entity and included in its Direct Debt.