Library Street Collective Announces representation of the Estate of Charles McGee

Photo by Sal Rodriguez

Library Street Collective is proud to announce its representation of the Estate of Detroit artist and educator Charles McGee, who passed away in February of 2021 at the age of ninety six.

Born in Clemson, SC, in 1924, McGee moved to Detroit with his mother at the age of 10 during the Great Migration. Over a career that spanned 7 decades, McGee remained true to a practice that was informed by ‘the energy of life’: interdependence, equality, and connection among all living things. These ideas were the driving force in his life as well as his practice, and he moved across artistic styles and media with curiosity and ease over his lifetime. Through his work, McGee encouraged peace, balance, and harmony, with the desire to make the world a better place to live.

McGee was placed into fourth grade when he arrived in Detroit though he had never spent a day in school, having worked as a child on his grandparents’ sharecropping farm in North Carolina until his move North. He left high school to enroll in the Marines during World War II and was stationed in the South Pacific where he was part of the occupying force in Japan. On his return to Detroit after the war, McGee worked in the automotive industry while attending part-time classes at the Detroit Society for Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies) on the G.I. Bill. Despite working full time in the 50s and 60s as a welder, McGee was heavily involved in the African American art scene in Detroit. He focused his practice on charcoal drawings that depicted Black figures and addressed issues of inequality, as the Civil Rights movement increased in intensity around him.

“I feel we need to come together as a people. I think that has been and will be my dedication as long as I live”

— Charles McGee, 1988

In 1958, he and 14 other Black artists - led by Henri Umbaji King and Harold Neal - created Contemporary Studio, the second Black-operated visual art institution in Detroit. Contemporary Studio was at the forefront of what became Detroit’s Black cultural revolution during the 1960s. A leader of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes once said upon a visit to Detroit in 1964: “Harlem used to be the Negro cultural center of America. If Detroit has not already become so, it is well on its way to becoming it.” The flourishing of the arts in Detroit’s Black community was energized by the Civil Rights Movement. Detroit was a stronghold of Black Nationalist thought as advocated by Malcolm X, who lived in Lansing from 1928-1940 and retained strong ties to the area. As McGee recalled it, “I think there was always a Black consciousness, but I don’t think it was exhibited on the same scale as it has been since Stokely Carmichael or Malcolm X. I think Malcolm X was one of the people that really made Black people aware of Black people.” Malcolm X promoted the pursuit of knowledge of self and history for Black people in order to create their own identity, culture, and institutions. Inspired by these words, McGee spent many hours in Vaughn’s Bookstore, where he was first exposed to African literature, history, and culture.

The earliest influence of African art is seen in McGee’s work titled Huzuni, in 1960. The timing of this work marks him as one of the earlier African American artists of the post-WWII era to be inspired by his African heritage. According to artist and longtime friend McArthur Binion, “McGee was ‘Afro-centric’ long before anyone else,” and “The art world out there entered Detroit through Charles McGee.” McGee began to achieve national recognition for his work in 1966 and was part of a number of group shows presenting contemporary Black artists at the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in touring exhibitions with the Smithsonian and Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. In 1969 he was asked by the Detroit Artist’s Market to curate an exhibition of Black art that he titled Seven Black Artists, featuring works by McGee himself, Lester Johnson, Henri Umbaji King, Robert Murray, James Lee, Allie McGhee, Harold Neal, and Robert J. Stull. In the show’s catalog, McGee stated that “quality was the only criterion for inclusion,” and the show received rave reviews. Inspired by the response, McGee went on to open Gallery 7 the following year, representing many of the artists in the exhibition in addition to other nationally recognized names.

In conjunction with Gallery 7, McGee also founded the Charles McGee School of Art. The gallery’s artists volunteered their time teaching classes to all ages, with a focus on bringing art to Detroit’s young Black community. According to McGee, “Our idea was to educate hand, mind, and eye rather than giving the kids busy work to keep them off the streets. It was an art school, not an experiment in sociology.” In 1974, McGee organized a prison art program, in which artists from Gallery 7 taught classes at the Wayne County Jail. The school closed after 5 years of operation, but set in motion McGee’s decades-long commitment to teaching and improving the quality of life in Detroit through art. McGee created Untitled in 1974, an ambitious geometric mural he designed as part of a public art program that placed 14 works by Detroit artists in the downtown core.

Charles McGee

Prisms, 1971

Acrylic on canvas

44.5h x 60.75w in

In 1976, McGee was included in the Detroit Institute of Art’s Works in Progress II, which presented some of the city’s most accomplished artists, including Michael Luchs, Robert Wilbert, and David Barr. It was in this exhibition that he included Detroit and Urban Extract II, works from a series that addressed the debilitating impact of urban renewal focusing on the demolition of a low cost housing project and a commercial building. The commercial structure contained a barbershop that McGee frequented for many years and he featured pieces of the barbershop, as well as other demolished buildings in his works. Urban Extract II is a poignant freestanding piece composed of the shop’s window and its surrounding wall.

In 1978, McGee won a Michigan Arts Award granted by the Michigan Council for the Arts and Cultural Affairs, and helped found the Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit (CAID), serving as co-director the following year. In 1979, he was in a major exhibition at The Cranbrook Museum of Art, titled At Cranbrook, Downtown Detroit: Twenty-One Artists, and 1980 saw a mid-career retrospective of his work at the Midland Center for the Arts.

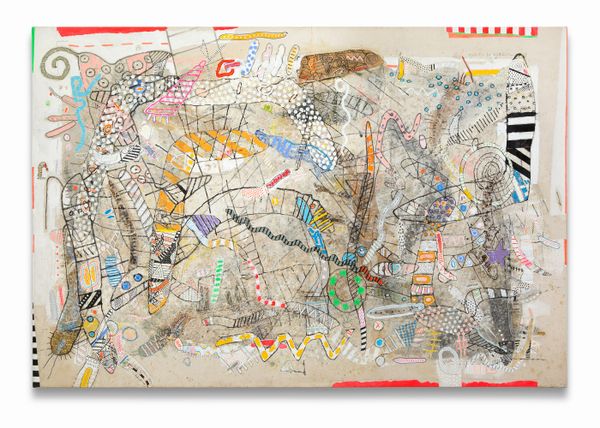

In the 1980s, McGee began to experiment with complex designs that drew from many aspects of his previous bodies of work, to create what would become his signature: patterns that dance inside the shapes of figures, animals, and organic forms. Movement is created in each piece through dynamic line work and repetition, pulsing with energy and rhythm. Keeping true to his lifelong respect for the earth, he incorporated natural elements and materials such as bean pods, soil, gypsum, and even his own dreadlocks.

Charles McGee

Patches of Time III, 1989

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

72.75h x 48.75w in

In 1993 and 1994, the DIA and the Dennos Museum at Northwestern Michigan College honored him with a show of his mature work from 1982 onward, titled Charles McGee: Seeing Seventy. In the following years, he reached his widest audiences, completing nearly 12 public commissions for universities, hospitals, government buildings, and public parks in Detroit and the surrounding municipalities. The first decade of the millennium also saw multiple solo exhibitions of McGee’s work, including those at the DIA, Eastern Michigan University, and the Marshall M Fredericks Sculpture Museum at Saginaw Valley State University.

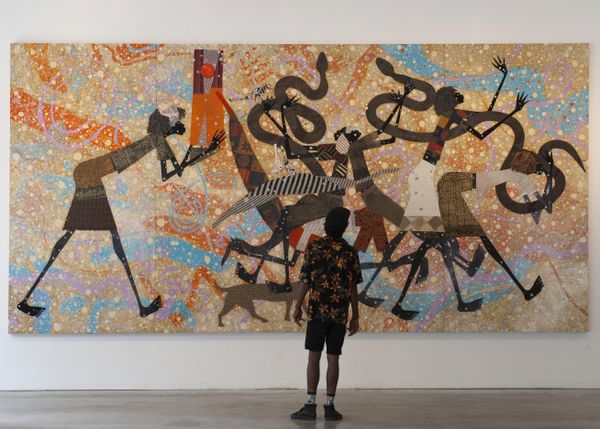

Charles McGee’s Play Patterns II as part of ‘Charles McGee: Still Searching’, 2017

McGee suffered a stroke in 2011 during preparation for his show at the Marshall M. Fredericks Museum while working on Play Patterns II, a monumental mixed media painting sized 10 x 20 ft. After leaving the hospital, he enlisted the help of assistants to complete the piece and it became one of the most iconic works of his career. In 2016, McGee was commissioned by the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History to create United We Stand, a massive sculpture for their elevated plaza (and a placement he had been eyeing since the museum opened in 1997). It was one of the great honors of his lifetime to create the sculpture to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1967 civil disturbance in Detroit.

Charles McGee, United We Stand, 2016, at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History

In 2017, Library Street Collective began working closely with McGee, organizing a retrospective titled Charles McGee: Still Searching, and commissioned him to design his largest mural, Unity, on the side of the 28Grand building in downtown Detroit at 92 years old. In McGee’s final years, the gallery brought his work to collectors across the country and featured him in art fairs and group exhibitions, including a show curated by his friend McArthur Binion, Homemade. Since his passing in early 2021, the gallery has worked alongside his daughter, Lyndsay McGee, to assemble a collection of his remaining works, as well as organize available documents, studies, catalogs, and press from his prolific career.

Library Street Collective will soon announce upcoming projects featuring the extraordinary art and legacy of Charles McGee, and looks forward to sharing his work for years to come.