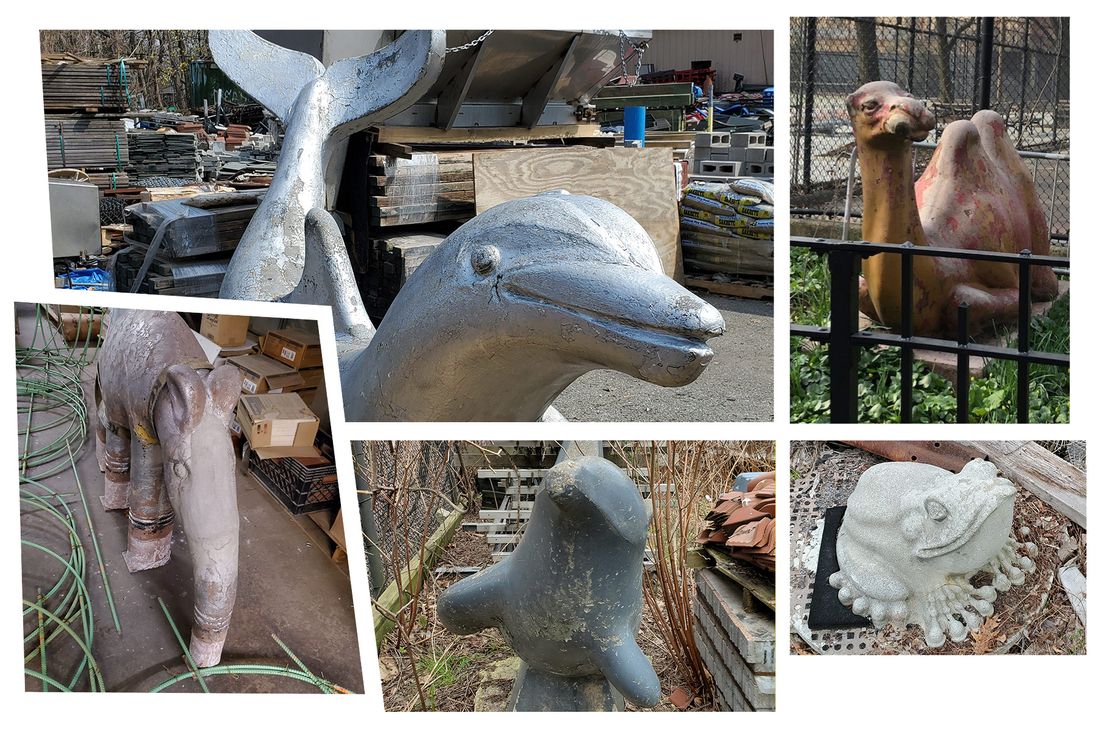

This fall, a camel, an aardvark, a frog, and two dolphins are moving into a new retirement community in Queens. The menagerie of sculptures have served in playgrounds across the city for decades, and have endured the tough love of countless children. These five animals, removed from playgrounds during renovations, will be the first of many to begin living out their golden years at the new “NYC Parks Home for Retired Playground Animals” in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. The crumbling creatures, some of which have had their paint stripped away from years of play, will sit in a new grove-turned sculpture garden just north of the Unisphere that the Parks Department describes as “a contemplative space for the animal retirees and their visitors to enjoy.” No more climbing will be allowed — “They’ve had enough,” a mock-up of the signage explains.

If you grew up in New York City or raised kids here, the hundreds of animal statues peppered across the city’s parks likely figure in your playground memories. Since the 1980s, they’ve been fixtures of the system — they are playthings, geographic markers, backdrops at birthday parties and picnics. In many cases, neighborhood parks become known by the names of the animals that reside within them. (Turtle Playground in Flushing has lime-green mid-century-modern tortoises.) But over the decades, many of the figures have been removed and discarded to make way for new play equipment and accessibility features. Now, instead of being reduced to rubble, these statues will join the new retirement home, which is currently under review by the local community boards. Years from now, as more retirees arrive, this shaded corner of Flushing Meadows may be the only place in the city where these beloved animals can still be seen — and where the most enduring legacy of former Parks commissioner Henry J. Stern will be retired too.

Stern — who ran the Parks Department from 1983 to 1990 and again from 1994 to 2000 — was a highly public eccentric, and he was fascinated with animals, both alive and figurative. (Stern died in 2019, at 83.) His golden retriever, Boomer, often accompanied him on official Parks business. When Stern drove through the city, he would crane his neck up to marvel at the carved stone creatures on façades and corbels as he passed by. He even founded the somewhat tongue-in-cheek American Association for the Advancement and Appreciation of Animals in Art and Architecture — the 7A, for short — which occasionally held group visits to animal-adorned structures across the city. During the years he oversaw New York’s Department of Parks and Recreation, under mayors Koch and Giuliani, Stern turned his obsession into a mandate: Park designers were tasked with including animal art in every new and renovated playground and park in the city.

Sometimes it was a simple touch, like hoofprints stamped in concrete or mosaics of mammals on tiled walls. But more often than not, it was some sort of play sculpture. Elephants on the Upper East Side. Bears in Bay Ridge. Sea lions in Long Island City. Adrian Benepe, who worked with Stern and served as commissioner of the parks department under Mayor Bloomberg, said it was Stern’s “eccentric love” for animals in the built environment that fueled his mission to share that art with young New Yorkers in parks, and a desire to give children as much exposure to animals as possible. “It used to be that there were more opportunities to see wild animals, so I think that was also part of Stern’s M.O.: We’re removing animals from zoos and circuses, but we can keep their memory alive for children in parks,” he said.

The city’s acquisition of parks animal art really picked up during Stern’s second term, under Giuliani. Between 1994 and 1996 alone, 300 concrete critters and other animal works were added to the city’s parks at the cost of $300,000. (Today, about 100 of those animals remain.) But as Stern began spending more and more taxpayer money on decorative animals, some elected officials openly wondered if this was the best use of taxpayer money. For instance, a single bronze coyote placed in Van Cortlandt Park in 1997 cost a whopping $20,000 — money that could have gone toward more prosaic park needs, like fixing broken swings and busted park benches. Sometimes the animal art could feel forced, like three Dalmatian silhouettes intended as a memorial for firefighter Louis Valentino in Carroll Park — which felt like such a stretch that the plan was rejected by public design officials. It didn’t seem to matter to Stern, so long as an animal was somewhere.

And Stern’s biggest opposition was the New York City Art Commission (now known as the Public Design Commission), which reviews the designs of municipal works like park projects. Michele Bogart, who was a commissioner from 1999 to 2003, says she opposed many of Stern’s plans not because of the price tag but because the statues were mostly generic catalogue items that lacked a meaningful connection to the parks they were placed in. But in order to meet Stern’s animal-art decree, officials would often shoehorn these sculptures into parks with ridiculous arguments for why a certain piece was fitting — a practice that Bogart and others on the commission found offensive. One project manager proposed a 20-foot-high bison for Greeley Square in Midtown simply because it was Horace Greeley who coined the slogan “go west, young man.” Another time, Parks officials proposed installing a group of mail-order Holstein cows near the reconstruction of a concession stand in Flushing Meadow Park because the Borden’s Milk pavilion occupied the spot during the 1939 World’s Fair. (Bogart chronicled these and other outlandish examples in her book The Politics of Urban Beauty.) “We’d smack our heads every time this stuff came in and we routinely disapproved of those components because they were cheap and they were really disrespectful, in our view, to the community,” she said. Bogart once found herself retreating under her desk during a commission meeting when officials proposed putting imprints of chicken and pig feet in a park in the Bronx’s West Farms neighborhood. She could not control her incredulous laughter.

But if the commission thought Stern was ridiculous, he didn’t really seem to care. In 1999, the city proposed a refresh of Seward Park on the Lower East Side that included a bronze statue of a Siberian husky named Togo, one of two dogs responsible for the 1925 dash to bring anti-diphtheria serum to Nome, Alaska. Parks officials argued that the park’s namesake, William Henry Seward, who brokered the U.S.’s purchase of Alaska, gave it a link to the state, and thus to Togo. The art commission wasn’t buying it, and shot the statue down. A couple of years later, when Bogart visited the newly refurbished space, she discovered Togo in the bushes. “They stuck that dog next to a fence in the greenery just so that it would get put there; it wasn’t even in a place that kids could play on,” she said.

It wasn’t that Stern wanted nothing but animals and the art commission wanted none at all. And by no means were all the sculptures mail-order pieces with no real provenance. There are 14 beloved fiberglass hippopotamuses in a Riverside Park playground that were created by sculptor Bob Cassilly Jr. in 1993. Three bronze bears are the focal point of Ruth and Arthur Smadbeck-Heckscher East Playground in Central Park — a 1990 work of the Art Deco sculptor Paul Manship, who is best known for Prometheus in Rockefeller Center. The commission was more on board for such projects, which they felt had real merit. “What we kept saying was, why can’t you have fewer works, but have really good ones? Really memorable ones?” Bogart said. “And that just wasn’t part of the game plan.”

The very need for the Home for Retired Playground Animals does highlight that these mail-order catalog pieces weren’t built to last. Still, Bogart is encouraged that the city is finding a way to reuse the animals instead of scrapping them altogether — though she wishes they’d touch them up before installing them in the new park. “I’m glad they’re acknowledging the original problem. It’s making lemonade out of lemons,” she said.

For city kids, the question of who designed a statue or if it’s particularly well made or not couldn’t matter less. The good statue is the one that’s at the neighborhood park, no matter how it ended up there. Every child in this city has a memory of triumphantly scaling one of these — for me, it’s the dolphin in the sand pit at Cobble Hill Park, five blocks from where I grew up. In that sense, Stern won: The animals have become part of New York’s design vernacular, and now that they’re so ingrained, they can’t be removed without an outcry. “The fact of the matter is that kids like them, and the playgrounds take on a special character because of the animals in them,” said Benepe. “Some thought they were kitschy. But Stern was just like, ‘who cares? It’s an animal; they’re kids.’ They just have a magic to them.”