Edward Tabor

Bethesda, MD, United States

|

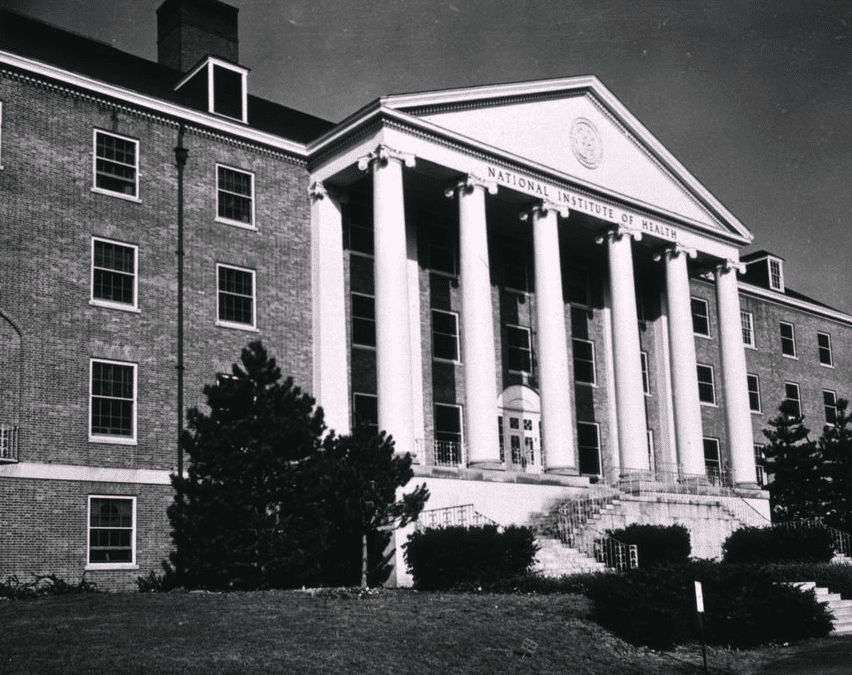

| The main administration building at the “National Institute of Health,” photographed sometime between 1940–1947, before the name was changed to “National Institutes of Health.” The original name can be seen under the cornice. From the “Images from the History of Medicine” collection at the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD. Public domain. |

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) supports medical research in non-government universities and hospitals and some small businesses. The cost and scope of these grants significantly exceed those of NIH’s own intramural program of clinics, wards, and laboratories. The NIH extramural grants today provide more than $37 billion1,2 for 50,0002 new and ongoing grants each year. These grants have led to many of the most important discoveries in medicine and the biological sciences in the past century. The program developed from the US government’s efforts to marshal science resources for World War II. Thus, preparations for war incidentally brought about great benefits in health.

Beginnings: Medical research contracts for World War II

With rare exceptions, the US government did not pay for medical research outside of its own laboratories before 1938.3,4 Most medical research in the US had been supported by pharmaceutical companies and a few private foundations, most notably the Rockefeller Foundation. By 1934, the Rockefeller Foundation provided two-thirds of all funding for medical and public health research in the US.5 In 1930, Congress created the “National Institute of Health” (later renamed the “National Institutes of Health”; the abbreviation “NIH” will be used here for both) by renaming the “Hygienic Laboratory” of the US Public Health Service (USPHS). It was conceived on a relatively small scale, but a series of additional laws passed by Congress during the 1930s and 1940s enlarged the structure of NIH, which ultimately affected the nature of the future grants program (Table 1).

| Table 1. Laws and events that shaped the NIH grants program |

||

| Year | Law | Action |

| 1930 | Ransdell Act | Created NIH within USPHS |

| 1937 | National Cancer Act | Created NCI within USPHS but independent of NIH |

| 1938–1940 | NIH and NCI moved to Bethesda campus | |

| 1944 | Public Health Service Act of 1944 (PL410) | Moved NCI into NIH; authorized USPHS (NIH) grants to universities and hospitalsa |

| 1948 | National Heart Act | Created heart and dental institutes at NIH; renamed NIH as “National Institutes of Health” |

| Abbreviations in Table 1: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NIH = National Institute(s) of Health; USPHS = US Public Health Service a Separately, a small number of cancer research grants had been issued by NCI since 1938, as authorized by the National Cancer Act of 1937. |

||

As World War II began in Europe, James Conant, president of Harvard University, had the idea of creating a government committee to stimulate scientific research for military preparedness. He brought the idea to Vannevar Bush, head of the Carnegie Institution, and Bush brought the idea to President Franklin Roosevelt. In 1940, Roosevelt created the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), with Vannevar Bush as its head, to oversee war-related scientific research and to award research contracts to civilian universities and institutes.

In June 1941, at Bush’s suggestion, Roosevelt created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) to oversee NDRC, with Bush as head. Conant now became head of NDRC, a position in which he later coordinated the US development of the atomic bomb. At the same time, a Committee on Medical Research (CMR) was created under OSRD to review medical needs and proposed medical research contracts. The director of CMR was Alfred N. Richards, who had been Vice President of Medical Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania and was a noted pharmacologist and researcher on kidney disease. CMR members included Dr. Rolla Eugene Dyer, director of NIH (representing the Surgeon General of the USPHS), as well as the Surgeons General of the Army and Navy, and others.

But CMR did not give grants for medical research, only contracts.6 CMR was concerned mainly with solutions to specific problems, and contracts gave the government more control of the projects, with the goals more clearly spelled out than would have been the case for grants.6 However, these contracts differed from conventional military procurement contracts because the end products were studies, of which the outcomes were unknown.

Supporting medical research in peacetime

Many people wanted government support of medical research to continue after the war. There was also a growing belief that good medical research could best be obtained by grants to researchers in universities and hospitals rather than contracts, based in part on the success of a small National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants program for cancer research that began in 1938, before NCI was part of NIH (Table 1). In July 1944, with the end of the war in sight, President Roosevelt signed the Public Health Service Act of 1944, which authorized the USPHS to “make grants in aid to universities, hospitals, laboratories, and other public or private institutions, and to individuals.”7

Also in 1944, Bush wanted to end the CMR program for medical research contracts, and Dyer suggested that these contracts become part of the NIH portfolio.5,6 NIH converted the contracts to grants at the end of 1945,8 which helped establish the principle of using grants for medical research. By the end of 1946, the extramural grants run by NCI also became part of the overall NIH research grants portfolio.8 CMR was disbanded on December 31, 1946.9

In 1945, NIH created the Office of Research Grants (changed in 1946 to the Division of Research Grants). Dr. Cassius J. Van Slyke was appointed director on January 1, 1946. Van Slyke had recently come to NIH to work on venereal disease research, but had a heart attack in 1945. Dyer thought that directing the new grants program might be suitable for Van Slyke during his recovery. Van Slyke later quipped that Dyer thought it would be “an incidental part time, left hand, lower drawer of the desk sort of activity.”5 It soon became apparent that it would be a major undertaking and Van Slyke was spending twelve to fourteen hours a day on it.8 Van Slyke remained head of the Division of Research Grants until 1948.

Van Slyke predicted that the NIH grants “may have early and profound effects upon the course of medical history and the national health” and would result in “enormous savings of public and private money” by preventing and curing diseases.10 Working with a small staff, Van Slyke created the administrative structure and the grants procedures that would remain in use for the next three-quarters of a century. In the beginning, the Office of Research Grants consisted of Van Slyke, his assistant Ernest Allen, and two secretaries. The first grant applications under the new system were solicited by a letter from Van Slyke and Allen to the deans of all US medical schools.

The first new NIH grant5 was awarded in 1945 (for fiscal year [FY] 1946) for a study at the University of Utah of the inheritance of muscular dystrophy. Money to support this study had been attached to the budget by a senator from Utah for $92,000 ($1.5 million in 2022 dollars11). Dyer deliberately selected this study for the first use of the new grant-giving authority, and he had it reviewed by the National Advisory Health Council (NAHC), the main NIH advisory council at that time. (A second proposal considered at the same meeting of the NAHC was rejected.)

Initially, the grant funds were only given for one year at a time; research projects lasting longer than one year required submission of a new application each year. These subsequent applications were subject to the same review process, but with the understanding that they would be reviewed favorably as long as progress was being made. Investigators were free to change the research plan and planned expenditures without restriction as long as the funds were used for research and in accordance with their university’s rules. Equipment purchased with grant funds remained the property of the grantee institution after the end of the grant.10,12

Expansion of NIH grants

| Table 2. Growth of study sections |

||

| Year | Number of Study Sections | Number of Reviewers |

| 19468,10 | 21 | >250 |

| 197413 | 38 | 6774 |

| 19878 | 67 | 2,200 |

| 202214 | >250 | >18,000 |

By the end of 1946, the main processes of the NIH extramural grant program were in place and were very close in design to those still used today. Almost immediately after the creation of the grants program, it began to expand (Table 2,3). By October 1946, NIH had funded 264 extramural research grants for a total of $3,900,000 ($55 million in 2022 dollars) at seventy-seven universities in twenty-six states (including the projects transferred from CMR).10 By 1951, 25% of medical research publications originating in colleges and universities included acknowledgement of at least some USPHS (i.e. NIH) support; however, at the time, individual NIH grants often provided only partial support.18 By 1955, NIH was awarding $54 million per year in grants for research, training, and construction of research facilities8 ($599 million in 2022 dollars). In the words of one writer, “By 1950, the team was in place, the premises were established, the purposes rolled easily off all administrators’ tongues; the system was ready and rolling.”8

| Table 3. Growth of expenditures for NIH extramural grants: A historical overview |

||

| Fiscal Yeara | Total Cost of NIH Grants | Total in 2022 Dollars11 |

| 194610 | $ 3.9 million | $ 63 million |

| 19568 | $ 54 million | $ 599 million |

| 19744 | $ 604 million | $ 3.8 billion |

| 19874 | $ 2.4 billion | $ 6.4 billion |

| 20222 | $ 37 billion | $ 37 billion |

| a The US government’s fiscal year ran from July 1 to June 30 in the years from 1842 through 1976, and from October 1 through September 30 from 1977 to the present.15 | ||

Most NIH research grants were “Research Project Grants,” later called “R01 grants.” Each supported an individual lead investigator’s research project. Other types of grants, including training grants, program project grants, and small business grants, were added later. However, R01 grants always represented a majority of the grants.1,16

The expansion of extramural grant funding and the expansion of the number of NIH institutes (each institute dedicated to a specific disease area) occurred in parallel. By 1950, NIH had six institutes. The number of institutes continued to increase, reaching fifteen by 1970 and twenty-seven by 1998. Each institute had a role in seeking and funding grants in its disease area.

Creating a system to review grant applications

There was a philosophy at NIH that all grant applications should be reviewed by experts from outside the government to avoid potential restriction of scientific innovation and conflicts of interest. This concept of outside review of grants may have been inspired by a temporary federal program in 1879–1883, when a National Health Board gave federal grants to universities for yellow fever research under the oversight of a committee with a majority of nongovernmental members.4 More directly, the concept was influenced by the success of the peer-review system that had been set up by CMR for its medical research contracts.4 In addition, the Public Health Service Act of 1944 had specified that outside experts should review USPHS (NIH) grants.

To find expert reviewers for the first grant applications, Van Slyke and Allen used a copy of the directory American Men of Science to identify potential reviewers among experts in each subject area. In the beginning, Allen recalled, “we would write to three or four of these people and get their opinions on the merit of the proposal. We then took [their assessments of] the proposals to the National Advisory Health Council.”8

NIH quickly developed a formal two-tiered system of review. Grant applications were submitted to the Division of Research Grants. Then the first level of review was conducted by “study sections” of outside experts, who met in person to review, suggest changes, and (in the early years) to approve or disapprove the applications. By 1950, an early version of a rating system was implemented, whereby study sections gave each application a numerical score instead of recommending approval or disapproval, which permitted funding to be given in order of appraised merit.4 The number of study sections steadily increased to address the greater numbers of applications (Table 2). In addition, the study sections were expected to survey the existing research in their subjects in order to find neglected areas in which to encourage future research. Most of the study sections met quarterly, a few weeks in advance of the quarterly meetings of the relevant advisory council. Each study section was coordinated by an “executive secretary”; at first, these included some NIH intramural laboratory scientists, but soon these were replaced by full-time executive secretaries.

Initially, a second-level review was performed by outside experts on one of the three NIH advisory councils: the National Advisory Cancer Council, the National Advisory Mental Health Council, and NAHC for all other research areas.10 By 1955, each of the eight NIH institutes in existence at that time had its own advisory council of outside experts to conduct the second level of review for grants in their disease areas.8 The study sections and the advisory councils also formulated research policy by means of the criteria they used to select which grant applications to approve and fund.

NIH research grants today

Today, NIH grants make up more than 84% of the $45 billion FY2022 NIH budget, or more than $37 billion.2 These funds support 50,000 new and ongoing grants and more than 300,000 scientists.2

NIH grants are now overseen by the Center for Scientific Review, which interfaces with the twenty-four NIH institutes and centers that give grants (of a total of twenty-seven institutes and centers). Study sections are now officially called “scientific review groups,” although the term “study section” is still widely used. The executive secretaries are now called “scientific review officers.” Today, study section meetings typically are held about three months before the relevant advisory council meeting;17 applications are reviewed and given a numerical ranking. The applications are then sent to that institute’s advisory council for a secondary review.

Most applications today are investigator-initiated, in which the applicant conceived and developed the research idea. Other applications are submitted in response to an announcement by the relevant NIH institute or center seeking applications for research on a specific medical problem. An “R01” grant application supporting an individual investigator’s project16 can be either investigator-initiated or submitted in response to an announcement, and the grant has a three- to five-year duration.

Conclusions

The NIH medical research grants program arose from a World War II program for medical research contracts. The grants were designed to encourage independent research on important medical and biological topics, and in this they have exceeded expectations. They have funded many of the most important medical advances of our times.

These successes have been due, in part, to the guiding philosophy of the program. As stated by Van Slyke, the NIH grants should be “a medical research program of scientists and by scientists” that maintains “the integrity and independence of the research worker and his freedom from control, direction, regimentation, and outside interference.”10

References

- National Institutes of Health. NIH RePORT [sic]: Budget and spending: Research grants. 2022. Table 101. Viewed at https://report.nih.gov/funding/nih-budget-and-spending-data-past-fiscal-years/budget-and-spending. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- National Institutes of Health. What we do: Budget. National Institutes of Health website, 2022. Viewed at nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/budget. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- Harden VA. Inventing the NIH: Federal Biomedical Research Policy, 1887-1937. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1986.

- Mandel R. A Half Century of Peer Review: 1946-1996. Division of Research Grants, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 1996.

- Schneider WH. The origin of the medical research grant in the United States: The Rockefeller Foundation and the NIH extramural funding program. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 2015; 70(2):279-311.

- Swain DC. The rise of a research empire, 1930 to 1950. Science 1962; 138(3546):1233-1237, 1962.

- Willcox AW. The Public Health Service Act, 1944. Bulletin, August 1944, pages 15-17. Viewed at Social Security Administration website, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v7n8/v7n8p15.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- Strickland SP. The Story of the NIH Grants Programs. University Press of America, Lanham, MD, 1989.

- Schmidt CF. Alfred Newton Richards, 1876-1966, a biographical memoir. Biographical Memoirs. National Academy of Sciences, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1971, pages 271-318.

- Van Slyke CJ. New horizons in medical research. Science 1946; 104(2711): 559-567.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI [Consumer Price Index] inflation calculator. Viewed at https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- National Institutes of Health. Commonly asked questions about equipment under grants. NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, vol. 24, no. 15, April 28, 1995. Viewed at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not95-121.html. Accessed August 26, 2022.

- Miles RE, Jr. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Praeger, New York, 1974.

- Center for Scientific Review, NIH. CSR data and evaluations. 2022. Viewed at https://public.csr.nih.gov/AboutCSR/Evaluations. Accessed August 16, 2022.

- Heniff B, Jr. The Federal Fiscal Year. Report for Congress 98-325. Congressional Research Service, 2008. Viewed at https://budgetcounsel.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/98-325.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2022.

- National Institutes of Health. NIH Grants & Funding: NIH Research Project Grant Program (R01). 2022. Viewed at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm. Accessed August 30, 2022.

- NIH Center for Scientific Review. Center for Scientific Review website, 2022. Viewed at https://www.csr.nih.gov/RevPanelsAndDates/RevDates.aspx. Accessed August 24, 2022.

- Endicott KM and Allen EM. The growth of medical research 1941-1953 and the role of Public Health Service research grants. Science 1953; 118(3065): 337-343.

EDWARD TABOR, M.D. has worked at the US Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute (NIH), and Fresenius Kabi. He has published widely on viral hepatitis, liver cancer, and pharmaceutical regulatory affairs.

Leave a Reply